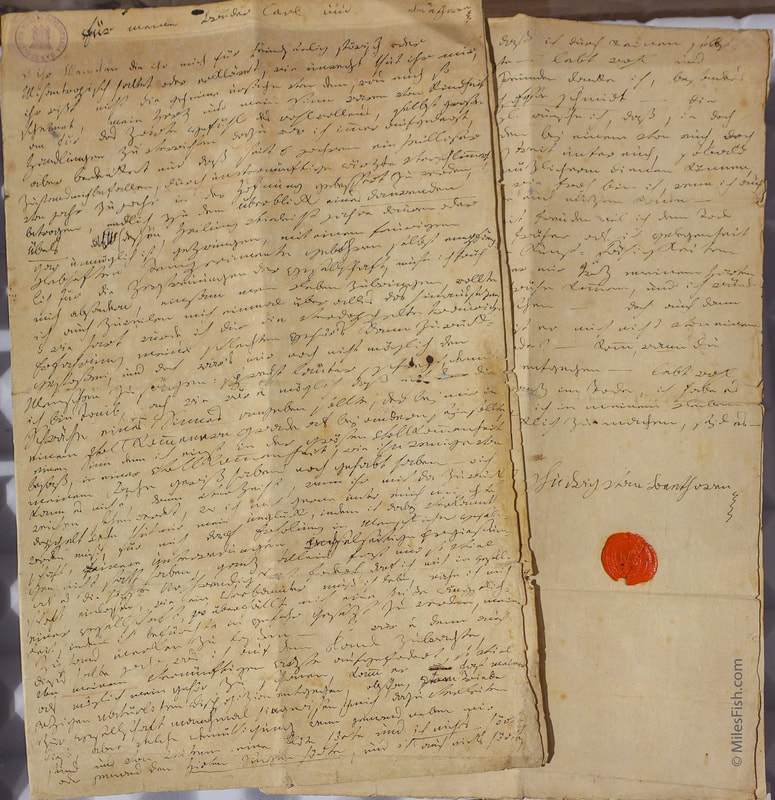

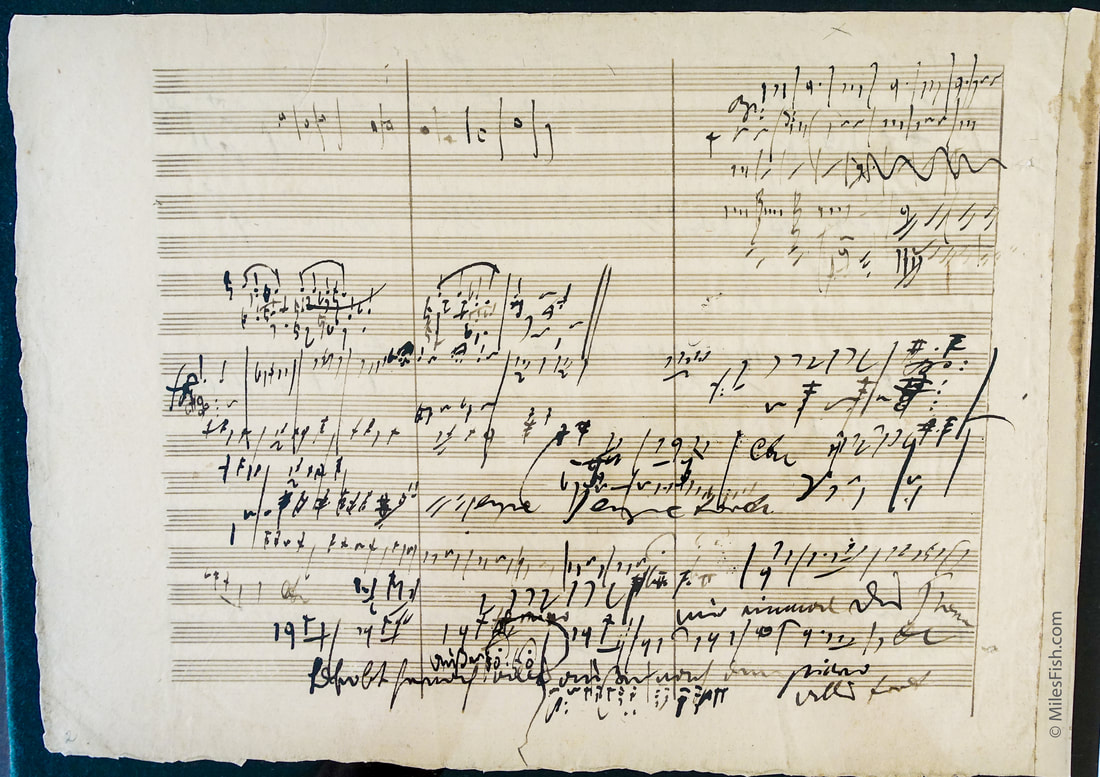

Abbe Joseph Gelinck letter

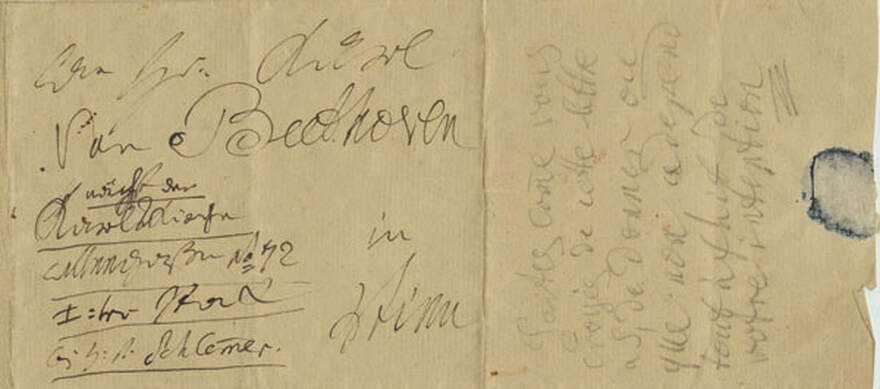

Dad Letter

Haydn/Elector Letter

Piano Trio published comments

Ferdinand Ries Bonaparte Letter

Google "some qualities of music in the Classical Era"

- Balanced

- Clear melodies

- Clear-cut musical phrases and cadences

- Emotions carefully controlled

- Emphasis on beauty, elegance and balance

- Careful attention to form

- Refined expression

- Surface beauty

- Restrained

- Aristocratic (sometimes perhaps “puffed-up")

Eroica: Two Critics React

Eroica: Ferdinand Ries Reacts

BEETHOVEN—Ages/Dates Timeline

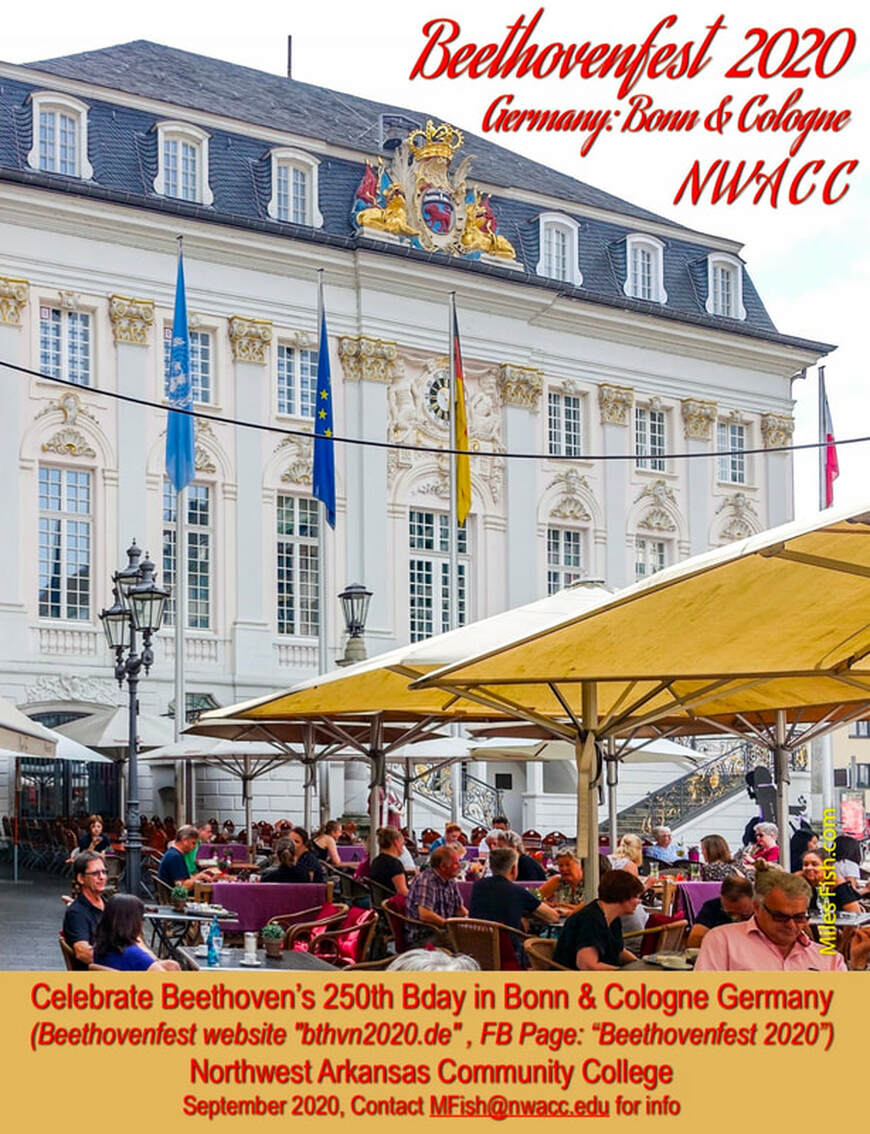

Born 1770 in Bonn Germany

Age 3—Grandad dies (1773)

Age 4—Brother Carl born (1774)

Age 6—Brother Johann born (1776)

Age 8—first public performance in Cologne (dad advertised he was 6) (1778)

Age 12—first published compositions: Variations on a march by Dressler (1783)

Age 17—receives stipend to go to Vienna to study with Mozart. (1787) (?) Returns home after a couple of weeks in Vienna due to his mom’s ill health back in Bonn. She dies after his return. He remains in Bonn for 5 years

Age 19—writes the elector asking for part of his father’s salary to provide for his brothers (1789)

Age 20—Haydn passes through Bonn and meets Beethoven. Offers to take him as a pupil if he moves to Vienna. (1790)

Age 21—Mozart dies in Vienna (1791)

Age 22—Moves to Vienna. Father dies back in Bonn. Beethoven never returns to Bonn (but remembers it fondly) (1792)

Age 23—begins lessons with Haydn says he learns “nothing” (1793)

Age 24—begins composing Piano Trios No. 1 (1794)

Age 25—plays trios for Haydn (1795)

Age 27—notices problems with hearing (1797)

Age 30—premiers 1st symphony (1799)

Age 31—Acknowledges in writing that something is wrong with his hearing. Moonlight sonata (named by Ludwin Rellstab..Lucern Swiss) (1800)

Age 32–2nd Symphony/ Heilianganstadt (1802)

Age 34—Eroica is first performed (1804)

Age 35—Appassionata and opera Leonore completed and banned…then un-banned (1805) Leonore unsuccessful premiers (France occupies Vienna)

Age 36—Revises Leonore (1806) another performance at Theater an Der Wien accuses management of cheating him. 4th symphony

Age 37—Fifth Symphony (1807)

Age 38—First performance of Fifty and Sixth (Pastoral) (1808)

Age 39—(1809) receive es annuity to stay in Vienna, Vienna bombarded by French, Haydn (age 77) dies.

Age 43—Wellington defeats French in Spain Beethoven writes the Battle Symphony op. 91 (1813)

Age 44—Fidelio performed (1814)

Age 47—Hammerklavier Sonata completed; Ninth began (1818)

Age 53—Ninth Symphony and Missa Solemnis premiered in Vienna (1824)

Age 54/55—Last quartets, Grosse Fugue Beethoven dies in March

SOME BEETHOVEN LETTERS

DAD LETTER (1793)

To Elector Maximilian Francis

Some years ago your Highness was pleased to grant a pension to my father, the Court tenor Van Beethoven, and further graciously to decree that…(A PORTION OF HIS) salary should be allotted to me, for the purpose of maintaining, clothing, and educating my two younger brothers, and also defraying the debts incurred by our father. It was my intention to present this decree to your Highness's treasurer, but my father earnestly implored me to desist from doing so, that he might not be thus publicly proclaimed incapable himself of supporting his family, adding that he would engage to pay me… quarterly, which he punctually did. After his death, however (in December last), wishing to reap the benefit of your Highness's gracious…(PENSION).., by presenting the decree, I was startled to find that my father had destroyed it. I therefore, with all dutiful respect, entreat your Highness to renew this decree, and to order the paymaster of your Highness's treasury to grant me the last quarter of this benevolent addition to my salary… I have the honor to remain, Your Highness's most

obedient and faithful servant, LUD. V. BEETHOVEN

HAYDN / ELECTOR LETTERS (1793)

Haydn left the Esterhazy estate in 1791

HAYDN

“Most Reverend Archbishop and Elector,

I am taking the liberty of sending your Reverence in all humility a few pieces of music . . . composed by my dear pupil Beethoven… They will, I flatter myself, be graciously accepted by your Reverence as evidence of his diligence . . . On the basis of these pieces, expert and amateur alike cannot but admit that Beethoven will in time become one of the greatest musical artists in Europe, and I shall be proud to call myself his teacher.

While I am on the subject of Beethoven, may your Reverence permit me to say a few words concerning his financial affairs? For the past year he was allowed 100 ducats (Du-cuts). That this sum was insufficient even for mere living expenses. Your Reverence may have had good reasons for sending him out into the great world with so small a sum. In order to prevent him from falling into the hands of usurers, I have advanced him cash, so that he owes me 500 florins. I now request that this sum be paid him. If your Reverence would allot him 1000 florins for the coming year, Your Reverence would free him of all anxiety . . . In the hopes that your Reverence will graciously accept this request of mine on behalf of my dear pupil, I am, with deepest respect, your Reverence’s most humble and obedient servant.

Joseph Haydn”

ELECTOR

“The music of young Beethoven which you sent me, with the exception of the fugue, was composed and performed here in Bonn before he departed to Vienna. Thus I cannot regard it as progress made in Vienna.

As far as his stipend is concerned, it does indeed amount to only 500 florins. But in addition to his salary here of 400 florins has been continuously paid to him; he received 900 florins for the year. I cannot, therefore, very well see why he is as much in debt as you say.

I am wondering, therefore, whether he had not better come back here in order to resume his work. For I very much doubt that he has made any progress in composition during his stay, and I fear that he will bring back nothing but debts.”

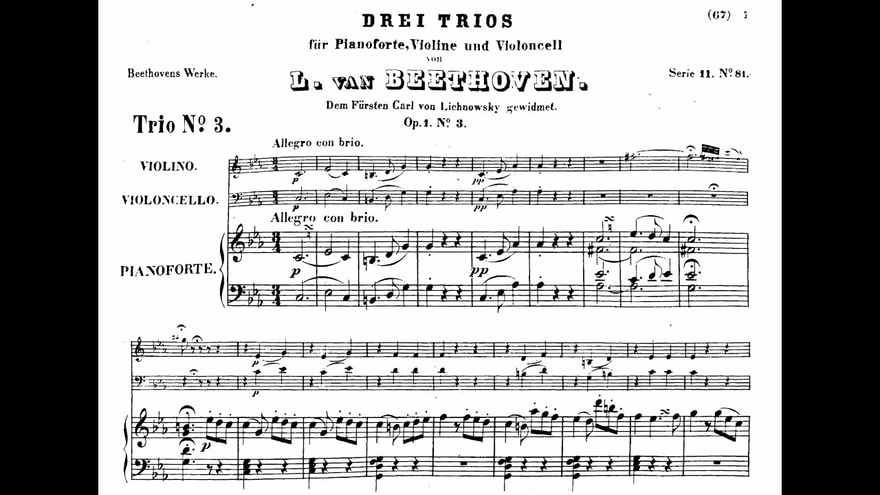

PIANO TRIOS

The Third in C minor

LA Philharmonic’s wonderful little article on this piece:

“Just as it seems to have settled finally into the home key of C minor in preparation for a big finish, it modulates down to B minor, in context the unlikeliest of keys and perhaps the biggest surprise of the whole Trio. Beethoven was fond of just-before-we-get-home detours (the sort of thing that critics found “strained and recherché”), probably because he had so much fun getting back on track. It is not the third Trio’s last surprise: the end itself is not what any listener is likely to expect."

Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven’s friend, who was there when Beethoven played them for Haydn wrote…

Haydn “said many fine things about the trios, but also cautioned that he would not have advised his pupil to publish No. 3, the C minor.”

Program note by Chris Darwin

"Haydn advised Beethoven not to publish the C minor trio. Beethoven took offense, thinking Haydn jealous and ill-disposed to him, though Haydn said he was simply trying to protect Beethoven from what he thought would be a hostile public response."

From Jan Swafford's book Anguish and Triumph

"Until this rival was in his grave, after the affair of the C Minor Trio Beethoven had very little good to say about Haydn or his music. One element inspiring his works to the end of his life (among many other elements) would be the rankling drive to challenge and outdo Haydn. In the event, Beethoven for once bit his tongue. There was no blowup over the C Minor Trio; relations between the two men remained polite, if strained."

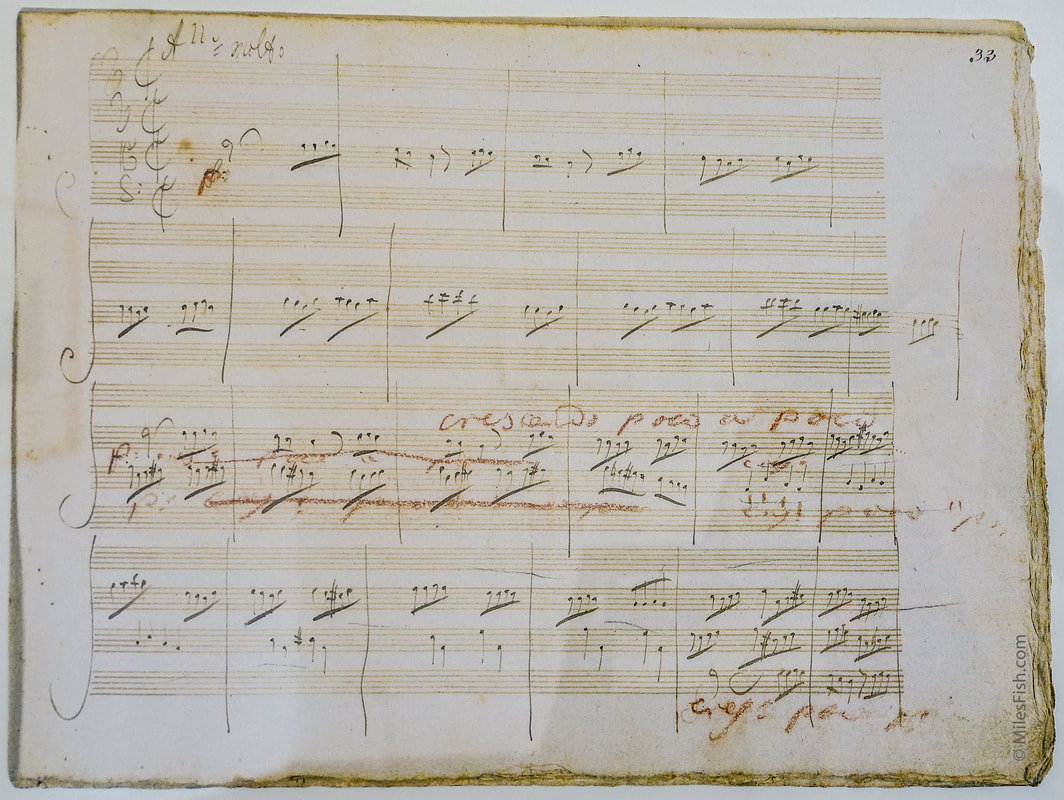

Beethoven wrote…

“When I re-read the manuscripts I wondered at my folly in collecting into a single work materials enough for twenty.”

The Third Symphony “Eroica”

Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven’s friend writes…

"I was the first to bring him the news that Bonaparte had proclaimed himself emperor, whereupon he flew into a rage and cried out: 'Is he too, then, nothing more than an ordinary human being? Now he, too, will trample on the rights of man, and indulge only his ambition!' Beethoven went to the table, took hold of the title page by the top, tore it in two, and threw it on the floor. The first page was rewritten and only then did the Symphony receive the title Sinfonia Eroica." Yet in a letter to his publisher not long later Beethoven admitted "the title of the symphony really is ‘Bonaparte’."

A local music critic wrote…

"At this concert I heard the new Beethoven symphony in E b conducted by the composer him- self…the symphony would improve immeasurably (it lasts an entire hour)2 if B. could bring himself to shorten it, and to bring more light, clarity, and unity into the whole. These are qualities that in Mozart’s Symphonies… passage(s) delight simply through a sense of order in apparent confusion….The symphony was also lacking a great deal else that would have enabled it to have pleased overall."

Another Critic wrote…

"…A new Beethoven Symphony in E b is for the most part so shrill and complicated that only those who worship the failings and merits of this composer with equal fire, which at times borders on the ridiculous, could find pleasure in it…."

And Another Critic wrote…

"That it is a work of genius, I hear from both admirers and detractors of Beethoven. Some people say that there is more in it than in Haydn and Mozart, that the Symphony-Poem has been brought to new heights! Those who are against it find that the whole lacks rounding out; they disapprove of the piling up of colossal ideas..."

Ferdinand Ries wrote at the time…

"In his (Beethoven’s) own opinion it is the greatest work that he has yet written. Beethoven played it for me recently, and I believe that heaven and earth will tremble when it is performed."

GENERAL CRITICISM

CRITICISM (June 1799)

"After having arduously worked his way through these quite peculiar sonatas, overladen with strange difficulties, he must admit that . . . he felt like a man who had thought he was going to promenade with an ingenious friend through an inviting forest, was detained every moment by hostile entanglements, and finally emerged, weary, exhausted, and without enjoyment. It is undeniable that Herr van Beethoven goes his own way. But what a bizarre, laborious way! Studied, studied, and perpetually studied, and no nature, no song. Indeed . . . there is

only a mass of learning here, without good method. There is obstinacy for which we feel little interest, a striving for rare modulations . . . a piling on of difficulty upon difficulty, so that one loses all patience and enjoyment."

CRITICISM (1799)

"His abundance of ideas . . . still too often causes him to pile up ideas without restraint and to arrange them in a bizarre manner so as to bring about an obscure artificiality or an artificial obscurity . . . [Yet] this critic . . . has learned to admire him more than he did at first."

FIDELIO

(from Jan Swaffords book)

Patiently Braun the head of the theater explained that while the expensive seats had been full, the galleries were not. Stalking up and down the room, Beethoven cried, “I don’t write for the multitude—I write for the connoisseurs!” The baron replied with something he should have known better than to say to Beethoven: “But the connoisseurs alone do not fill our theater. We need the multitude to bring in money, and since in your music you have refused to make any concession to it, you yourself are to blame . . . If we had given Mozart the same percentage of the receipts of his operas [that we gave you], he would have been rich.”

Historic Fidelio note:

Its successive versions (I – 1805, II – 1806, III – 1814) reflect the process of the composer’s struggle with the material and his truly painstaking work to produce the perfect dramatic form. The first version of the opera, a longish three-act Leonore, only lasted for three performances at the Theater an der Wien in 1805. A year later, the composer cut it down to two acts, but he still failed to achieve the expected success. Only the third attempt, based on a text modified by a new author, Georg Friedrich Treitschke, was constructive enough to end in a final version of 1814. The opera received the title of Fidelio and thus entered history of culture.

VURTUOSO

Abbe Joseph Gelinck

“Yesterday was a day I’ll remember! That young fellow must be in league with the devil. I’ve never heard anybody play like that! I gave him a theme to improvise on, and I assure you I’ve never heard even Mozart improvise so admirably. Then he played some of his own compositions which are marvelous—really wonderful—and he manages difficulties and effects at the keyboard that we never even dreamed of. “He’s a small, ugly, swarthy young fellow, and seems to have a willful disposition . . . His name is Beethoven.

BREAK-UPS

Beethoven

“You have been constantly and most vividly in my thoughts but—whenever I did so I was always reminded of that unfortunate quarrel; and my conduct at that time seemed to me really detestable. But what was done could not be undone. Oh, I would give a great deal to be able to blot out of my life my behavior at that time, a behavior which did me so little honor…

What a horrible picture you have shown me of myself! Oh, I admit that I do not deserve your friendship. You are so noble and well-meaning; and this is the first time that I dare not face you, for I have fallen far beneath you….what made me behave to you like that was no deliberate, premeditated wickedness on my part, but my unpardonable thoughtlessness . . . Yet, oh do let me say this in my defense, I really was always good and ever tried to be upright and honorable in my actions…

DAD LETTER (1793)

To Elector Maximilian Francis

Some years ago your Highness was pleased to grant a pension to my father, the Court tenor Van Beethoven, and further graciously to decree that…(A PORTION OF HIS) salary should be allotted to me, for the purpose of maintaining, clothing, and educating my two younger brothers, and also defraying the debts incurred by our father. It was my intention to present this decree to your Highness's treasurer, but my father earnestly implored me to desist from doing so, that he might not be thus publicly proclaimed incapable himself of supporting his family, adding that he would engage to pay me… quarterly, which he punctually did. After his death, however (in December last), wishing to reap the benefit of your Highness's gracious…(PENSION).., by presenting the decree, I was startled to find that my father had destroyed it. I therefore, with all dutiful respect, entreat your Highness to renew this decree, and to order the paymaster of your Highness's treasury to grant me the last quarter of this benevolent addition to my salary… I have the honor to remain, Your Highness's most

obedient and faithful servant, LUD. V. BEETHOVEN

HAYDN / ELECTOR LETTERS (1793)

Haydn left the Esterhazy estate in 1791

HAYDN

“Most Reverend Archbishop and Elector,

I am taking the liberty of sending your Reverence in all humility a few pieces of music . . . composed by my dear pupil Beethoven… They will, I flatter myself, be graciously accepted by your Reverence as evidence of his diligence . . . On the basis of these pieces, expert and amateur alike cannot but admit that Beethoven will in time become one of the greatest musical artists in Europe, and I shall be proud to call myself his teacher.

While I am on the subject of Beethoven, may your Reverence permit me to say a few words concerning his financial affairs? For the past year he was allowed 100 ducats (Du-cuts). That this sum was insufficient even for mere living expenses. Your Reverence may have had good reasons for sending him out into the great world with so small a sum. In order to prevent him from falling into the hands of usurers, I have advanced him cash, so that he owes me 500 florins. I now request that this sum be paid him. If your Reverence would allot him 1000 florins for the coming year, Your Reverence would free him of all anxiety . . . In the hopes that your Reverence will graciously accept this request of mine on behalf of my dear pupil, I am, with deepest respect, your Reverence’s most humble and obedient servant.

Joseph Haydn”

ELECTOR

“The music of young Beethoven which you sent me, with the exception of the fugue, was composed and performed here in Bonn before he departed to Vienna. Thus I cannot regard it as progress made in Vienna.

As far as his stipend is concerned, it does indeed amount to only 500 florins. But in addition to his salary here of 400 florins has been continuously paid to him; he received 900 florins for the year. I cannot, therefore, very well see why he is as much in debt as you say.

I am wondering, therefore, whether he had not better come back here in order to resume his work. For I very much doubt that he has made any progress in composition during his stay, and I fear that he will bring back nothing but debts.”

PIANO TRIOS

The Third in C minor

LA Philharmonic’s wonderful little article on this piece:

“Just as it seems to have settled finally into the home key of C minor in preparation for a big finish, it modulates down to B minor, in context the unlikeliest of keys and perhaps the biggest surprise of the whole Trio. Beethoven was fond of just-before-we-get-home detours (the sort of thing that critics found “strained and recherché”), probably because he had so much fun getting back on track. It is not the third Trio’s last surprise: the end itself is not what any listener is likely to expect."

Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven’s friend, who was there when Beethoven played them for Haydn wrote…

Haydn “said many fine things about the trios, but also cautioned that he would not have advised his pupil to publish No. 3, the C minor.”

Program note by Chris Darwin

"Haydn advised Beethoven not to publish the C minor trio. Beethoven took offense, thinking Haydn jealous and ill-disposed to him, though Haydn said he was simply trying to protect Beethoven from what he thought would be a hostile public response."

From Jan Swafford's book Anguish and Triumph

"Until this rival was in his grave, after the affair of the C Minor Trio Beethoven had very little good to say about Haydn or his music. One element inspiring his works to the end of his life (among many other elements) would be the rankling drive to challenge and outdo Haydn. In the event, Beethoven for once bit his tongue. There was no blowup over the C Minor Trio; relations between the two men remained polite, if strained."

Beethoven wrote…

“When I re-read the manuscripts I wondered at my folly in collecting into a single work materials enough for twenty.”

The Third Symphony “Eroica”

Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven’s friend writes…

"I was the first to bring him the news that Bonaparte had proclaimed himself emperor, whereupon he flew into a rage and cried out: 'Is he too, then, nothing more than an ordinary human being? Now he, too, will trample on the rights of man, and indulge only his ambition!' Beethoven went to the table, took hold of the title page by the top, tore it in two, and threw it on the floor. The first page was rewritten and only then did the Symphony receive the title Sinfonia Eroica." Yet in a letter to his publisher not long later Beethoven admitted "the title of the symphony really is ‘Bonaparte’."

A local music critic wrote…

"At this concert I heard the new Beethoven symphony in E b conducted by the composer him- self…the symphony would improve immeasurably (it lasts an entire hour)2 if B. could bring himself to shorten it, and to bring more light, clarity, and unity into the whole. These are qualities that in Mozart’s Symphonies… passage(s) delight simply through a sense of order in apparent confusion….The symphony was also lacking a great deal else that would have enabled it to have pleased overall."

Another Critic wrote…

"…A new Beethoven Symphony in E b is for the most part so shrill and complicated that only those who worship the failings and merits of this composer with equal fire, which at times borders on the ridiculous, could find pleasure in it…."

And Another Critic wrote…

"That it is a work of genius, I hear from both admirers and detractors of Beethoven. Some people say that there is more in it than in Haydn and Mozart, that the Symphony-Poem has been brought to new heights! Those who are against it find that the whole lacks rounding out; they disapprove of the piling up of colossal ideas..."

Ferdinand Ries wrote at the time…

"In his (Beethoven’s) own opinion it is the greatest work that he has yet written. Beethoven played it for me recently, and I believe that heaven and earth will tremble when it is performed."

GENERAL CRITICISM

CRITICISM (June 1799)

"After having arduously worked his way through these quite peculiar sonatas, overladen with strange difficulties, he must admit that . . . he felt like a man who had thought he was going to promenade with an ingenious friend through an inviting forest, was detained every moment by hostile entanglements, and finally emerged, weary, exhausted, and without enjoyment. It is undeniable that Herr van Beethoven goes his own way. But what a bizarre, laborious way! Studied, studied, and perpetually studied, and no nature, no song. Indeed . . . there is

only a mass of learning here, without good method. There is obstinacy for which we feel little interest, a striving for rare modulations . . . a piling on of difficulty upon difficulty, so that one loses all patience and enjoyment."

CRITICISM (1799)

"His abundance of ideas . . . still too often causes him to pile up ideas without restraint and to arrange them in a bizarre manner so as to bring about an obscure artificiality or an artificial obscurity . . . [Yet] this critic . . . has learned to admire him more than he did at first."

FIDELIO

(from Jan Swaffords book)

Patiently Braun the head of the theater explained that while the expensive seats had been full, the galleries were not. Stalking up and down the room, Beethoven cried, “I don’t write for the multitude—I write for the connoisseurs!” The baron replied with something he should have known better than to say to Beethoven: “But the connoisseurs alone do not fill our theater. We need the multitude to bring in money, and since in your music you have refused to make any concession to it, you yourself are to blame . . . If we had given Mozart the same percentage of the receipts of his operas [that we gave you], he would have been rich.”

Historic Fidelio note:

Its successive versions (I – 1805, II – 1806, III – 1814) reflect the process of the composer’s struggle with the material and his truly painstaking work to produce the perfect dramatic form. The first version of the opera, a longish three-act Leonore, only lasted for three performances at the Theater an der Wien in 1805. A year later, the composer cut it down to two acts, but he still failed to achieve the expected success. Only the third attempt, based on a text modified by a new author, Georg Friedrich Treitschke, was constructive enough to end in a final version of 1814. The opera received the title of Fidelio and thus entered history of culture.

VURTUOSO

Abbe Joseph Gelinck

“Yesterday was a day I’ll remember! That young fellow must be in league with the devil. I’ve never heard anybody play like that! I gave him a theme to improvise on, and I assure you I’ve never heard even Mozart improvise so admirably. Then he played some of his own compositions which are marvelous—really wonderful—and he manages difficulties and effects at the keyboard that we never even dreamed of. “He’s a small, ugly, swarthy young fellow, and seems to have a willful disposition . . . His name is Beethoven.

BREAK-UPS

Beethoven

“You have been constantly and most vividly in my thoughts but—whenever I did so I was always reminded of that unfortunate quarrel; and my conduct at that time seemed to me really detestable. But what was done could not be undone. Oh, I would give a great deal to be able to blot out of my life my behavior at that time, a behavior which did me so little honor…

What a horrible picture you have shown me of myself! Oh, I admit that I do not deserve your friendship. You are so noble and well-meaning; and this is the first time that I dare not face you, for I have fallen far beneath you….what made me behave to you like that was no deliberate, premeditated wickedness on my part, but my unpardonable thoughtlessness . . . Yet, oh do let me say this in my defense, I really was always good and ever tried to be upright and honorable in my actions…