THE EXTRAORDINARY OSPEDALE

The Exclusive Women’s World of Vivaldi’s Venice

Article and Photographs by Miles Dayton Fish

IT’S A MAN’S WORLD

In the 14th century, Venice’s St. Mark’s Cathedral became an epicenter of European music excellence and a magnet for music-loving travelers worldwide. Like the rest of Europe, the music world of St. Mark's was a man's world.

That was changing. But only in one city: the city-state Republic of Venice.

By the late 1600s, the hottest music ticket in Venice was no longer the St. Mark man’s world of Monteverdi and Giovanni Gabrieli but rather a women’s world attached to a smallish church near St. Mark’s where orphaned girls sang like angels.

These girls and women would become a model for future European music conservatories and a lasting prototype for women’s empowerment in music performance, education, and administration.

That was changing. But only in one city: the city-state Republic of Venice.

By the late 1600s, the hottest music ticket in Venice was no longer the St. Mark man’s world of Monteverdi and Giovanni Gabrieli but rather a women’s world attached to a smallish church near St. Mark’s where orphaned girls sang like angels.

These girls and women would become a model for future European music conservatories and a lasting prototype for women’s empowerment in music performance, education, and administration.

IT’S A WOMEN’S WORLD

A lifesize likeness of Vivaldi inside the Santa Maria della Pieta Church today

A lifesize likeness of Vivaldi inside the Santa Maria della Pieta Church today

In the 1600s and 1700s, most European women were housewives. They cleaned, cooked, and worked beside their husbands on farms and city shops or ran their homes as noblemen’s wives. Professional jobs for women were never an option, and their choices were mostly limited to a marriage or a nunnery.

But this was different for some women in the city-state Republic of Venice.

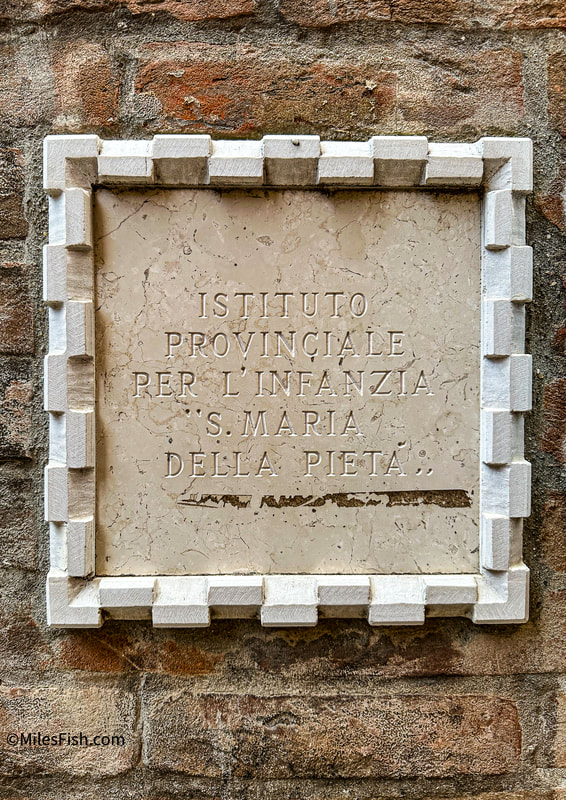

In Venice, four charitable Ospedali Grandi (literal translation: large hospitals) accommodated the city's benevolent needs. One of the four--Ospedale della Pietà--was established as a sanctuary for abandoned girls. It is best known today for the years Antonio Vivaldi was employed there (1703-1715 and 1723-1740).

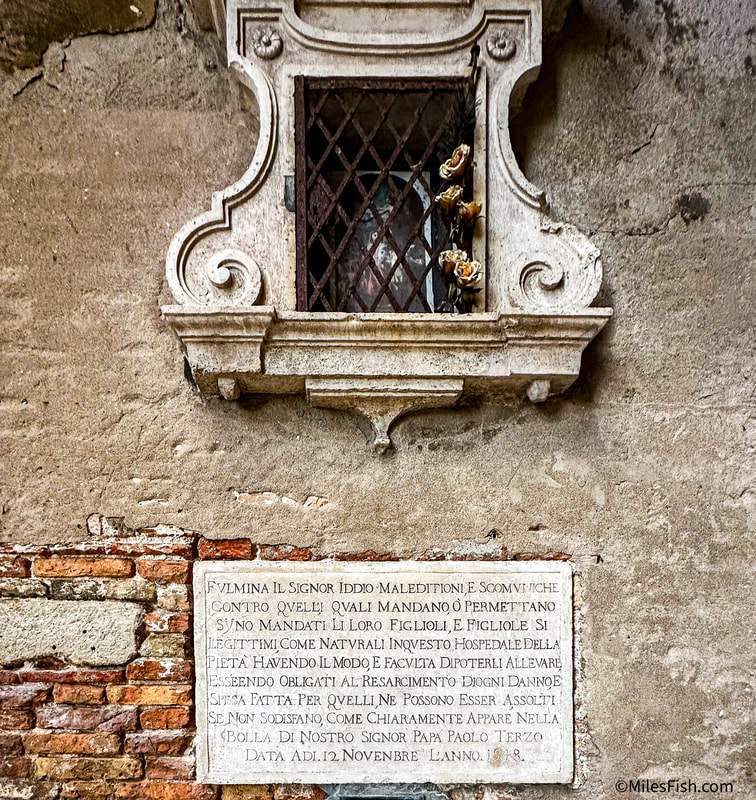

In 1335, the Venetian government established the all-girl Pietà to house, feed, clothe, and educate Venice’s female foundlings (abandoned children who must be cared for by others). From the start, their education included music, but that was only the beginning at Ospedale La Pietà. Over the years, music would become became the prime focus in the lives of the girls and women who lived, studied, taught, and worked there.

The Ospedali was run by secular committees and financed by nobles, city citizens, and wealthy merchants. Later, European aristocrats on the Grand Tour helped support the ensembles financially. The vocal and instrumental ensembles were initially used to aid liturgical worship at the adjacent Santa Maria della Pietà Church. The choir and orchestra performed on balconies above the church’s sanctuary floor. The performers’ faces were obscure behind the balconies’ iron grillwork and lace curtains.

But this was different for some women in the city-state Republic of Venice.

In Venice, four charitable Ospedali Grandi (literal translation: large hospitals) accommodated the city's benevolent needs. One of the four--Ospedale della Pietà--was established as a sanctuary for abandoned girls. It is best known today for the years Antonio Vivaldi was employed there (1703-1715 and 1723-1740).

In 1335, the Venetian government established the all-girl Pietà to house, feed, clothe, and educate Venice’s female foundlings (abandoned children who must be cared for by others). From the start, their education included music, but that was only the beginning at Ospedale La Pietà. Over the years, music would become became the prime focus in the lives of the girls and women who lived, studied, taught, and worked there.

The Ospedali was run by secular committees and financed by nobles, city citizens, and wealthy merchants. Later, European aristocrats on the Grand Tour helped support the ensembles financially. The vocal and instrumental ensembles were initially used to aid liturgical worship at the adjacent Santa Maria della Pietà Church. The choir and orchestra performed on balconies above the church’s sanctuary floor. The performers’ faces were obscure behind the balconies’ iron grillwork and lace curtains.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

The performers’ faces were intentionally concealed because the church and state prohibited females from public performances throughout the Christian world. The grillwork and lace covered balconies allowed the Pietà women to be “heard and not seen.” Still, women making music in public remained a rare and audacious concept and was undoubtedly part of the scandalous allure of Venice, where scandal thrived.

But as in other goings-on in Venice, the church, given the substantial amount of money the Republic brought to the Vatican City coffers, blessed these angels singing in public as they continued to become one of Venice’s fastest-growing performance moneymakers.

As mentioned, La Pietà was first endowed by the city-state and civic donations. Then, as its popularity grew, wealthy merchant benefactors became involved, and still later, European aristocrats on the Grand Tour helped support the ensembles financially.

And finally, in Venice’s true entrepreneurial spirit, Santa Maria della Pietà Church became one of the world’s first churches to charge admission for entry and sell printed programs.

La Pietà moved from being a purely charity organization to a for-profit, quid-pro-quo profitable enterprise.

As music taste shifted from sacred to secular, La Pietà accommodated these changes in audience expectations. The church became a virtual concert hall featuring the rare performance of female voices accompanied by female instrumentalists, led by a female conductor.

Upon hearing La Pieta's women’s choir, one visiting writer remarked…. “It is like I hear the sounds of angels; I must be in heaven,” to which his companion responded, “No, you’re in Venice.”

But as in other goings-on in Venice, the church, given the substantial amount of money the Republic brought to the Vatican City coffers, blessed these angels singing in public as they continued to become one of Venice’s fastest-growing performance moneymakers.

As mentioned, La Pietà was first endowed by the city-state and civic donations. Then, as its popularity grew, wealthy merchant benefactors became involved, and still later, European aristocrats on the Grand Tour helped support the ensembles financially.

And finally, in Venice’s true entrepreneurial spirit, Santa Maria della Pietà Church became one of the world’s first churches to charge admission for entry and sell printed programs.

La Pietà moved from being a purely charity organization to a for-profit, quid-pro-quo profitable enterprise.

As music taste shifted from sacred to secular, La Pietà accommodated these changes in audience expectations. The church became a virtual concert hall featuring the rare performance of female voices accompanied by female instrumentalists, led by a female conductor.

Upon hearing La Pieta's women’s choir, one visiting writer remarked…. “It is like I hear the sounds of angels; I must be in heaven,” to which his companion responded, “No, you’re in Venice.”

OLD MONEY LONG GONE

Venice's glory days as the world’s first international financial center and wealthiest city had passed. By the 1600s and 1700s, the city-state republic was in economic decline. However, it remained a prime source of European culture, fine art, purveyor of luxury goods, and great music. Music in Venice remained an undiminished source of joy and pride and beckoned wealthy travelers worldwide. The entrepreneurial Venetians replaced their lost trade revenue with an agressive quest for tourism gold.

During Vivaldi’s time, Venice became the world’s first travel destination city. Music—secular and sacred—contributed to this tourism revenue godsend bonanza.

During Vivaldi’s time, Venice became the world’s first travel destination city. Music—secular and sacred—contributed to this tourism revenue godsend bonanza.

PAY-PER-VIEW OPERA

Venice's remaining opera house

Venice's remaining opera house

In 1637, Venice’s Teatro di San Cassiano became Europe’s first opera house to offer entry for the price of admission. Elsewhere on the continent, opera performances were available only to nobles and members of the court. But Venice was a republic, not a monarchy, and there were no court or elitist restrictions on who could and could not enjoy opera.

Venice's DNA included a love for music performances and an entrepreneurial spirit to make it profitable. One of the city's wealthy merchant families opened San Cassiano as a commercial venture. It was a financial success, and soon, other for-profit opera houses followed suit and entertained the public regardless of class or social standing.

Venice, at this time, offered a glimpse of the beginning of the global concert society that was to come. In the process, the Republic briefly became the music performance capital of the world, and the star in Venice’s musical crown was the Ospedale della Pietà.

Venice's DNA included a love for music performances and an entrepreneurial spirit to make it profitable. One of the city's wealthy merchant families opened San Cassiano as a commercial venture. It was a financial success, and soon, other for-profit opera houses followed suit and entertained the public regardless of class or social standing.

Venice, at this time, offered a glimpse of the beginning of the global concert society that was to come. In the process, the Republic briefly became the music performance capital of the world, and the star in Venice’s musical crown was the Ospedale della Pietà.

SCHOOL DAYS

At La Pietà, 40-60 of the most talented girls rehearsed and performed in the prestigious Figlie del coro (Daughters of the Choir). The clergy was often responsible for classroom instruction, while women administrators and women musicians controlled the day-to-day running of the school including the music programs. Male teachers such as Vivaldi were rarely appointed, and when they were, they were designated for a tenure of one year at a time.

Alison Curcio stated in the article “Venice’s Ospedali Grandi” that most of the employees of the La Pietà were female. “The structure of the ospedali relied on female leadership and encouraged the education of females. The ospedale developed educated women, virtuosic female musicians, and leading female administrators.”

Daily, the girls received a rigorous music education consisting of vocal and instrumental performance, sight-singing, and ear-training. Those who chose to remain at the school could stay with the chorus and further their education, performance skills, and explore music composition.

In short, they received an education and lived a lifestyle they could have only received in Venice. And this lifestyle, which could last a lifetime, was in a radically feminist universe.

La Pieta became one of the world’s first organizations to present girls and women with long-term music education, study, and performance opportunities. Girls often grew to become old women at La Pieta.

Alison Curcio stated in the article “Venice’s Ospedali Grandi” that most of the employees of the La Pietà were female. “The structure of the ospedali relied on female leadership and encouraged the education of females. The ospedale developed educated women, virtuosic female musicians, and leading female administrators.”

Daily, the girls received a rigorous music education consisting of vocal and instrumental performance, sight-singing, and ear-training. Those who chose to remain at the school could stay with the chorus and further their education, performance skills, and explore music composition.

In short, they received an education and lived a lifestyle they could have only received in Venice. And this lifestyle, which could last a lifetime, was in a radically feminist universe.

La Pieta became one of the world’s first organizations to present girls and women with long-term music education, study, and performance opportunities. Girls often grew to become old women at La Pieta.

AGE IS JUST A NUMBER

At age 24, women of the coro were eligible to advance to positions with more responsibilities, and at 30, they could assume even more duties that included teaching. At 40, they could retire and transfer to a convent. However, most remained and performed at the advanced age of 60 and older, as it would have been difficult to give up a lifetime of music-making

The women of La Pietà were allowed to marry and leave at any time, with dowries in place for those who did. But very few married and left the Ospedale. Two possible reasons: 1) they did not want to give up their lifestyle and their life of music, and 2) it seems that men at that time did not want a wife who was his educational superior.

The women of La Pietà were allowed to marry and leave at any time, with dowries in place for those who did. But very few married and left the Ospedale. Two possible reasons: 1) they did not want to give up their lifestyle and their life of music, and 2) it seems that men at that time did not want a wife who was his educational superior.

THEY SAID YOU WERE HIGH-CLASS

One of the remaining architectural details of La Pieta "Vivaldi's Staircase"

One of the remaining architectural details of La Pieta "Vivaldi's Staircase"

In the beginning, the girls of the Ospedale della Pietà were of the lowest class. This changed, however, as La Pietà’s reputation for music performance gained international celebrity status. La Pietà eventually began accepting middle-class girls based on their musical abilities and the musical needs of the chorus. Later, the highest-class girls of noble families were admitted as it was believed that Venice’s La Pietà offered upper-class girls an education superior to any other European city.

At La Pietà, music dissolved barriers of class in Venetian society. It drew international attention to performances by the lowest-class of people in Venice and recruited higher-class girls with musical talent to perform in these same ensembles.

Some classroom studies may have been socially segregated, but not in the music or performances of the Figlie del Coro or the orchestra.

In short, nowhere else in the world could women find what was offered at La Pietà: an educational society of women from all different social classes living and working together to create and enjoy the study and public performance of music.

It was revolutionary.

And it’s important to note that not all the women at La Pietà were performers. Women also held administrative and teaching positions and the staff numbered as many as 200 women. The organization offered women administrative and teaching positions unavailable elsewhere in Europe. It provided female musicians a quality music education and the unheard-of opportunities to perform regularly in public. Women held La Pietà paying jobs that provided them an independent life over marriage or convent.

At La Pietà, music dissolved barriers of class in Venetian society. It drew international attention to performances by the lowest-class of people in Venice and recruited higher-class girls with musical talent to perform in these same ensembles.

Some classroom studies may have been socially segregated, but not in the music or performances of the Figlie del Coro or the orchestra.

In short, nowhere else in the world could women find what was offered at La Pietà: an educational society of women from all different social classes living and working together to create and enjoy the study and public performance of music.

It was revolutionary.

And it’s important to note that not all the women at La Pietà were performers. Women also held administrative and teaching positions and the staff numbered as many as 200 women. The organization offered women administrative and teaching positions unavailable elsewhere in Europe. It provided female musicians a quality music education and the unheard-of opportunities to perform regularly in public. Women held La Pietà paying jobs that provided them an independent life over marriage or convent.

THE TIMES ARE A-CHANGING

Vivaldi's residence (now the Hotel Rio), where he composed the Gloria (RV589)

Vivaldi's residence (now the Hotel Rio), where he composed the Gloria (RV589)

As the popularity of liturgical performances was replaced with popular secular instrumental music, the Pietà was dedicated as a performance model for changing musical taste.

Later in his career, Vivaldi, who had written his Gloria (RV589) and Nisi Dominus (RV608) for the coro’s liturgical performances, was required to write two monthly concerti to meet the demand for instrumental performances at La Pieta. He went on to write his Violin Concerto in D minor (RV 248), the Violin Concerto in B-flat (RV 363), and the Mandolin Concerto in C (RV 425), Oboe Concerto in C Major RV 450, among other works for La Pieta.

La Pietà remained involved with progressive changes in instrumentation. In the mid-1700s, the orchestra introduced “new” diverse and rare instruments such as clarinet, flute, horn, and timpani into its orchestra.

Unsurprisingly, future remodling plans constantly considered making the sanctuary of the adjoining Santa Maria della Pieta Church more acoustically adept for music performance.

The church became a virtual concert hall, the performance home for the girls’ sanctuary next door. In Venice, concerts occurred every night in private palaces, music halls, opera houses, churches, and music institutions. However, the performances of Ospedali della Pietà’s women remained the most coveted tickets in town and one of Venice's most bankable moneymakers for decades.

Later in his career, Vivaldi, who had written his Gloria (RV589) and Nisi Dominus (RV608) for the coro’s liturgical performances, was required to write two monthly concerti to meet the demand for instrumental performances at La Pieta. He went on to write his Violin Concerto in D minor (RV 248), the Violin Concerto in B-flat (RV 363), and the Mandolin Concerto in C (RV 425), Oboe Concerto in C Major RV 450, among other works for La Pieta.

La Pietà remained involved with progressive changes in instrumentation. In the mid-1700s, the orchestra introduced “new” diverse and rare instruments such as clarinet, flute, horn, and timpani into its orchestra.

Unsurprisingly, future remodling plans constantly considered making the sanctuary of the adjoining Santa Maria della Pieta Church more acoustically adept for music performance.

The church became a virtual concert hall, the performance home for the girls’ sanctuary next door. In Venice, concerts occurred every night in private palaces, music halls, opera houses, churches, and music institutions. However, the performances of Ospedali della Pietà’s women remained the most coveted tickets in town and one of Venice's most bankable moneymakers for decades.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

The water taxi entrance to the Metropole Hotel. According to historian Micky White, Vivaldi would have used this water entry as he rarely walked to La Pieta

The water taxi entrance to the Metropole Hotel. According to historian Micky White, Vivaldi would have used this water entry as he rarely walked to La Pieta

The Ospedale was the template for future music institutions in the Western world. The Royal Academy of Music London (1822) was the first English music school that solely trained both boys and girls to be professional musicians. Felix Mendelssohn, who 1843 founded the Leipzig Conservatory, was influenced by his teacher Carl Zelter, who had begun a school modeled upon the Ospedali.

In his Choral Journal article “Angles of Song: An Introduction to Musical Life at the Venetian Ospedali,” Christopher Eanes writes that the impression the ospedali and their musicians had made on the thousands of spectators was never forgotten. “…as a result of their wide-spread fame throughout Europe in the eighteenth century, they served as models for what was to become the modern conservatory, first in Paris, London, and Leipzig, and eventually worldwide.”

The girls and women of the Ospedale della Pietà were part of what became known as the “Noblest educational experience in Europe.” From its humble beginnings, it formed the core of Venetian music culture. It “rose to the rank of the greatest European center for vocal and instrumental music” and established itself as an extraordinary music universe that belonged almost exclusively to women.

In his Choral Journal article “Angles of Song: An Introduction to Musical Life at the Venetian Ospedali,” Christopher Eanes writes that the impression the ospedali and their musicians had made on the thousands of spectators was never forgotten. “…as a result of their wide-spread fame throughout Europe in the eighteenth century, they served as models for what was to become the modern conservatory, first in Paris, London, and Leipzig, and eventually worldwide.”

The girls and women of the Ospedale della Pietà were part of what became known as the “Noblest educational experience in Europe.” From its humble beginnings, it formed the core of Venetian music culture. It “rose to the rank of the greatest European center for vocal and instrumental music” and established itself as an extraordinary music universe that belonged almost exclusively to women.

END

References

Barbier, Patrick, "Vivaldi’s Venice"

London, Editions Grasset et Fasquelle, 2003

Curcio, Alison (2010) "Venice's Ospedali Grandi: Music and Culture in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries"

Nota Bene:Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 2.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/notabene/article/download/6556/5280/12328&ved=2ahUKEwjHgejr7bWGAxXTA9sEHYunAA4QFnoECDwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3MQ6_h35arjO2wPi5bRP61 ,

Ables, Mollie, "Musicians Networks in Early Modern Venice"

https://echo.orpheusinstituut.be/article/musicians-networks-in-early-modern-venice

Hunter, Anne Schuster, "Venice’s Improbable All-Girl Baroque Bands"

https://tempestadimare.org/blog/women-behind-screens/, 2023

Images of Venice website, Ospedali Grandi of Venice, https://imagesofvenice.com/ospedali-grandi/

Wise, Brian, "Vivaldi and La Pieta"

https://www.exploreclassicalmusic.com/vivaldi-and-the-ospedale-della-piet

Eanes, Christopher, "Angles of Song: An Introduction to Musical Life at the Venetian Ospedali"

https://acda-publications.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/choral_journals/February_2009_Eanes,C.pdf, 2009

Dias, Luis, "Vivaldi’s Foundlings and the Healing Power of Music"

https://luisdias.wordpress.com/2017/12/17/vivaldis-foundlings-and-the-healing-power-of-music/ ,017

And

Conversations with Micky White in Venice

London, Editions Grasset et Fasquelle, 2003

Curcio, Alison (2010) "Venice's Ospedali Grandi: Music and Culture in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries"

Nota Bene:Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 2.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/notabene/article/download/6556/5280/12328&ved=2ahUKEwjHgejr7bWGAxXTA9sEHYunAA4QFnoECDwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3MQ6_h35arjO2wPi5bRP61 ,

Ables, Mollie, "Musicians Networks in Early Modern Venice"

https://echo.orpheusinstituut.be/article/musicians-networks-in-early-modern-venice

Hunter, Anne Schuster, "Venice’s Improbable All-Girl Baroque Bands"

https://tempestadimare.org/blog/women-behind-screens/, 2023

Images of Venice website, Ospedali Grandi of Venice, https://imagesofvenice.com/ospedali-grandi/

Wise, Brian, "Vivaldi and La Pieta"

https://www.exploreclassicalmusic.com/vivaldi-and-the-ospedale-della-piet

Eanes, Christopher, "Angles of Song: An Introduction to Musical Life at the Venetian Ospedali"

https://acda-publications.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/choral_journals/February_2009_Eanes,C.pdf, 2009

Dias, Luis, "Vivaldi’s Foundlings and the Healing Power of Music"

https://luisdias.wordpress.com/2017/12/17/vivaldis-foundlings-and-the-healing-power-of-music/ ,017

And

Conversations with Micky White in Venice

Faculty Development

Northwest Arkansas Community College

One College Drive, Bentonville, AR 72712

____________________