Lecture #13

The World's a Stage: OPERA

______________________________________________________________

OPERA

Four centuries of opera

The 17th century: the baroque period and the beginnings of opera

Opera was born in Italy at the end of the 16th century. A group of Florentine musicians and intellectuals, la camerata fiorentina, were fascinated by Ancient Greece and opposed to the excesses of Renaissance polyphonic music. They wanted to revive what was thought to be the simplicity of ancient tragedy. The first opera still performed today was La favola d’Orfeo (The Legend of Orpheus), composed by Monteverdi in 1607, 400 years ago. In the first operas, the intention was to make music subservient to the words. They were made up of successive recitatives with a small instrumental accompaniment, punctuated by musical interludes. After Florence and Rome, Venice rapidly became the centre of opera, where the first commercial opera house opened in 1637, thus making the art form accessible to a wider public. Opera soon spread throughout Europe, and in 1700 Naples, Vienna, Paris and London were major operatic centres.

The 18th century: Bel Canto and classical reform

Two opera forms developed in the 18th century: opera seria and opera buffa. Opera seria, or serious opera, was akin to tragedy and often inspired from mythology. The important solo parts were often sung by the famous castrati. Ariodante by Händel (1735) is an example of opera seria. On the contrary, the comic opera buffastaged ordinary characters and dealt with lighter topics. Main roles were played by tenors or basses. An example of this type, which appeared at the beginning of the 18th century, was Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro (1786).

Whereas the first operas endeavoured to highlight the words, the end of the baroque period was that of great bel canto tunes. This ‘beautiful singing’ gave primacy to vocal virtuosity. In reaction, a more simple style in which text and music were more closely allied, throve from the end of the 18th century. In classical operas, singing served the dramatic idea, not the reverse. They also used choruses and ensembles to stress the collective nature of human emotions. Christoph Willibald Gluck initiated this reform (Iphigenia in Tauris, 1779) which then influenced many composers.

The 19th century: Verdi and Wagner, the golden age of opera

With the rise of nationalism, different traditions developed in different countries. The romantic era began with the works of the German composer Carl Maria von Weber (Der Freischütz, 1821 ;Oberon, 1826). The genre intermixed serious and comic opera traits, absorbing aspects of symphonic music, with subjects drawn from contemporary life and recent history. Richard Wagner revolutionised opera in the second half of the century, from The Flying Dutchman (1843) to Parsifal (1882) and the four operas of the Ring of the Nibelung (1869-1876). Wagner gathered music, drama, poetry and staging in what he called ‘music drama’. In his operas, the orchestra became part of the story, and he frequently used the leitmotiv, a musical phrase associated with a character, an event or an idea.

In Italy, the voice remained predominant. The bel canto tradition went on, combined with opera buffa characters and themes. Examples are Rossini’s The Barber of Seville (1816), Bellini’s Norma (1831) or Donizetti’s The Love Potion, 1832). Giuseppe Verdi was the last great Italian composer of the 19th century. In a passionate and vigorous style, he wrote pieces which allied spectacular show and subtle emotions (La Traviata, 1853, Aïda, 1871).

A specific tradition developed in Russia and Eastern Europe, inspired by history (Boris Godunov, Mussorgsky, 1869-1874) or from national literature (Eugene Onegin, Tchaikovsky, 1879). In France, ‘Grand Opéra’ flourished, with great scenic effects, action and ballet. Opéra Comique, which included spoken dialogues, was also very popular (Bizet’s Carmen, 1875).

The 20th century: the rise of individuals

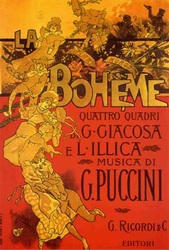

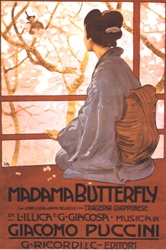

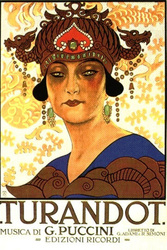

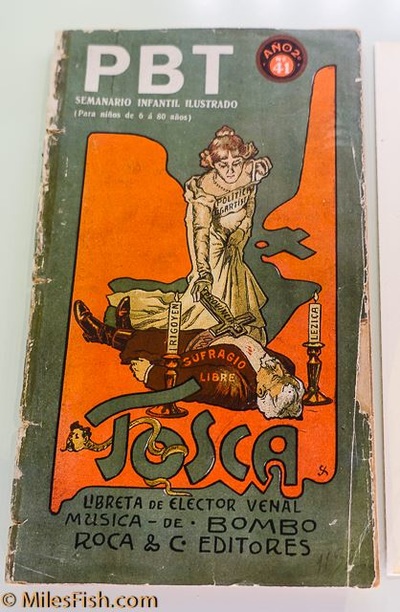

The beginning of the 20th century continued the trends of the late 19th. Puccini was the last great Italian composer, who wrote among others Tosca (1900), Madam Butterfly (1904) and Turandot (1926). Other famous operas of the time were Pelleas and Melisande by Debussy (1902), Salome by Strauss (1905), and The Cunning Little Vixen by Janacek (1924).

Later, individual works rather than general trends appeared. Alban Berg’s operas (Wozzeck, 1925, Lulu, 1937) contrasted with Kurt Weill’s works, inspired from jazz and other popular music (The Threepenny Opera, 1928). Benjamin Britten composed ‘traditional’ operas like Peter Grimes (1945), but also chamber operas.

The 21st century: a score still to be written…

Today, the operatic offer is more varied than ever. Staging and settings have become key elements of new productions. The great pieces of the repertoire are repeatedly reinterpreted and still very successful. They are presented next to new contemporary operas and earlier rediscovered works. In this way, opera is in permanent evolution, for the enjoyment of the widest public.

OPERA

Four centuries of opera

The 17th century: the baroque period and the beginnings of opera

Opera was born in Italy at the end of the 16th century. A group of Florentine musicians and intellectuals, la camerata fiorentina, were fascinated by Ancient Greece and opposed to the excesses of Renaissance polyphonic music. They wanted to revive what was thought to be the simplicity of ancient tragedy. The first opera still performed today was La favola d’Orfeo (The Legend of Orpheus), composed by Monteverdi in 1607, 400 years ago. In the first operas, the intention was to make music subservient to the words. They were made up of successive recitatives with a small instrumental accompaniment, punctuated by musical interludes. After Florence and Rome, Venice rapidly became the centre of opera, where the first commercial opera house opened in 1637, thus making the art form accessible to a wider public. Opera soon spread throughout Europe, and in 1700 Naples, Vienna, Paris and London were major operatic centres.

The 18th century: Bel Canto and classical reform

Two opera forms developed in the 18th century: opera seria and opera buffa. Opera seria, or serious opera, was akin to tragedy and often inspired from mythology. The important solo parts were often sung by the famous castrati. Ariodante by Händel (1735) is an example of opera seria. On the contrary, the comic opera buffastaged ordinary characters and dealt with lighter topics. Main roles were played by tenors or basses. An example of this type, which appeared at the beginning of the 18th century, was Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro (1786).

Whereas the first operas endeavoured to highlight the words, the end of the baroque period was that of great bel canto tunes. This ‘beautiful singing’ gave primacy to vocal virtuosity. In reaction, a more simple style in which text and music were more closely allied, throve from the end of the 18th century. In classical operas, singing served the dramatic idea, not the reverse. They also used choruses and ensembles to stress the collective nature of human emotions. Christoph Willibald Gluck initiated this reform (Iphigenia in Tauris, 1779) which then influenced many composers.

The 19th century: Verdi and Wagner, the golden age of opera

With the rise of nationalism, different traditions developed in different countries. The romantic era began with the works of the German composer Carl Maria von Weber (Der Freischütz, 1821 ;Oberon, 1826). The genre intermixed serious and comic opera traits, absorbing aspects of symphonic music, with subjects drawn from contemporary life and recent history. Richard Wagner revolutionised opera in the second half of the century, from The Flying Dutchman (1843) to Parsifal (1882) and the four operas of the Ring of the Nibelung (1869-1876). Wagner gathered music, drama, poetry and staging in what he called ‘music drama’. In his operas, the orchestra became part of the story, and he frequently used the leitmotiv, a musical phrase associated with a character, an event or an idea.

In Italy, the voice remained predominant. The bel canto tradition went on, combined with opera buffa characters and themes. Examples are Rossini’s The Barber of Seville (1816), Bellini’s Norma (1831) or Donizetti’s The Love Potion, 1832). Giuseppe Verdi was the last great Italian composer of the 19th century. In a passionate and vigorous style, he wrote pieces which allied spectacular show and subtle emotions (La Traviata, 1853, Aïda, 1871).

A specific tradition developed in Russia and Eastern Europe, inspired by history (Boris Godunov, Mussorgsky, 1869-1874) or from national literature (Eugene Onegin, Tchaikovsky, 1879). In France, ‘Grand Opéra’ flourished, with great scenic effects, action and ballet. Opéra Comique, which included spoken dialogues, was also very popular (Bizet’s Carmen, 1875).

The 20th century: the rise of individuals

The beginning of the 20th century continued the trends of the late 19th. Puccini was the last great Italian composer, who wrote among others Tosca (1900), Madam Butterfly (1904) and Turandot (1926). Other famous operas of the time were Pelleas and Melisande by Debussy (1902), Salome by Strauss (1905), and The Cunning Little Vixen by Janacek (1924).

Later, individual works rather than general trends appeared. Alban Berg’s operas (Wozzeck, 1925, Lulu, 1937) contrasted with Kurt Weill’s works, inspired from jazz and other popular music (The Threepenny Opera, 1928). Benjamin Britten composed ‘traditional’ operas like Peter Grimes (1945), but also chamber operas.

The 21st century: a score still to be written…

Today, the operatic offer is more varied than ever. Staging and settings have become key elements of new productions. The great pieces of the repertoire are repeatedly reinterpreted and still very successful. They are presented next to new contemporary operas and earlier rediscovered works. In this way, opera is in permanent evolution, for the enjoyment of the widest public.

"Finale To Act I" by Puccini from La Bohème (start 5:30)

"Finale to Act I" by Puccini from La Boheme (all)

"Finale to Act I" (new) Puccini's La Boheme (all class at 18:00)

La Boheme (Full Version: start 16:00)

La Boheme Finale to Act 1 (subtitles)

Rent (Puccini's La Boheme in modern time)

Light my Candle

Viva la Boheme (start 1:00 end 4:16)

Seasons of love

"Humming Chorus" by Puccini from Madama Butterfly

Madame Butterfly 1. (1:00,00)

Madame Butterfly 2.

Turandot Explained

Turandot

"Nessun Dorma" from Turandot

"Nessun Dorma" Studio Cut

__________________________________________________________________________

Turandot Explained

______________

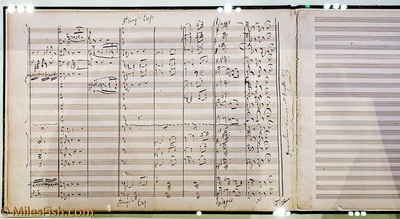

Rock Opera

________________________________________

________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

The World's a Stage

THE AMERICAN MUSICAL

The comic operettas of Gilbert & Sullivan (1871-1896) were witty, tuneful and exquisitely produced – leading to new standards of theatrical production. After Gilbert and Sullivan, the theatre in Britain and the United States was re-defined – first by imitation, then by innovation.

During the early 1900s, imports like Franz Lehar’s The Merry Widow (1907) had enormous influence on the Broadway musical, but American composers George M. Cohan and Victor Herbert gave the American musical comedy a distinctive sound and style. Then (1910s) Jerome Kern, Guy Boulton and P.G. Wodehouse took this a step further with the Princess Theatre shows, putting believable people and situations on the musical stage. During the same years, Florenz Ziegfeld introduced his Follies, the ultimate stage revue.

In the 1920s, the American musical comedy gained worldwide influence. Broadway saw the composing debuts of Cole Porter, Rodgers and Hart, the Gershwins and many others. The British contributed several intimate reviews and introduced the multi-talented Noel Coward. Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II wrote the innovative Showboat (1927) the most lasting hit of the 1920s.

The Great Depression did not stop Broadway – in fact, the 1930s saw the lighthearted musical comedy reach its creative zenith. The Gershwin’s Of Thee I Sing (1931) was the first musical ever to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Rodgers & Hart (On Your Toes - 1936) and Cole Porter (Anything Goes – 1934) contributed their share of lasting hit shows and songs.

The 1940s started out with business-as-usual musical comedy, but Rodgers & Hart’s Pal Joey and Weill and Gershwin’s Lady in the Dark opened the way for more realistic musicals. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma (1943) was the first fully integrated musical play, using every song and dance to develop the characters or the plot. After Oklahoma, the musical would never be the same – but composers Irving Berlin (Annie Get Your Gun - 1946) and Cole Porter (Kiss Me Kate – 1947) soon proved themselves ready to adapt to the integrated musical.

During the 1950s, the music of Broadway was the popular music of the western world. Every season brought a fresh crop of classic hit musicals that were eagerly awaited and celebrated by the general public. Great stories, told with memorable songs and dances were the order of the day, resulting in such unforgettable hits as The King and I, My Fair Lady, Gypsy and dozens more. These musicals were shaped by three key elements:

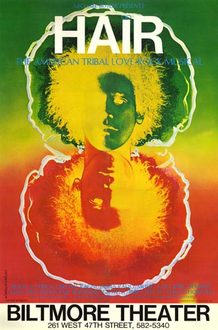

At first, the 1960s were more of the same, with Broadway turning out record setting hits (Hello, Dolly!, Fiddler on the Roof). But as popular musical tastes shifted, the musical was left behind. The rock musical "happening" Hair (1968) was hailed as a landmark, but it ushered in a period of confusion in the musical theatre.

Composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim and director Hal Prince refocused the genre in the 1970s by introducing concept musicals – shows built around an idea rather than a traditional plot. Company(1970), Follies (1972) and A Little Night Music (1973) succeeded, while rock musicals quickly faded into the background. The concept musical peaked with A Chorus Line (1974), conceived and directed by Michael Bennett. No, No, Nanette (1973) initiated a slew of popular 1970s revivals, but by decade’s end the battle line was drawn between serious new works (Sweeney Todd) and heavily commercialized British mega-musicals (Evita).

The public ruled heavily in favor of the mega-musicals, so the 1980s brought a succession of long-running "Brit hits" to Broadway – Cats, Les Miserables, Phantom of the Opera and Miss Saigon were light on intellectual content and heavy on special effects and marketing.

By the 1990s, new mega-musicals were no longer winning the public, and costs were so high that even long-running hits (Crazy for You, Sunset Boulevard) were unable to turn a profit on Broadway. New stage musicals now required the backing of multi-million dollar corporations to develop and succeed – a trend proven by Disney’s Lion King, and Livent’s Ragtime. Even Rent and Titanic were fostered by smaller, Broadway-based corporate entities.

As the 20th century ended, the musical theatre was in an uncertain state, relying on rehashed numbers (Fosse) and stage versions of old movies (Footloose, Saturday Night Fever), as well as the still-running mega-musicals of the previous decade. But starting in the year 2000, a new resurgence of American musical comedies took Broadway by surprise. The Producers, Urinetown, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Hairspray -- funny, melodic and inventively staged, these hit shows offered new hope for the genre.

THE AMERICAN MUSICAL

The comic operettas of Gilbert & Sullivan (1871-1896) were witty, tuneful and exquisitely produced – leading to new standards of theatrical production. After Gilbert and Sullivan, the theatre in Britain and the United States was re-defined – first by imitation, then by innovation.

During the early 1900s, imports like Franz Lehar’s The Merry Widow (1907) had enormous influence on the Broadway musical, but American composers George M. Cohan and Victor Herbert gave the American musical comedy a distinctive sound and style. Then (1910s) Jerome Kern, Guy Boulton and P.G. Wodehouse took this a step further with the Princess Theatre shows, putting believable people and situations on the musical stage. During the same years, Florenz Ziegfeld introduced his Follies, the ultimate stage revue.

In the 1920s, the American musical comedy gained worldwide influence. Broadway saw the composing debuts of Cole Porter, Rodgers and Hart, the Gershwins and many others. The British contributed several intimate reviews and introduced the multi-talented Noel Coward. Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II wrote the innovative Showboat (1927) the most lasting hit of the 1920s.

The Great Depression did not stop Broadway – in fact, the 1930s saw the lighthearted musical comedy reach its creative zenith. The Gershwin’s Of Thee I Sing (1931) was the first musical ever to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Rodgers & Hart (On Your Toes - 1936) and Cole Porter (Anything Goes – 1934) contributed their share of lasting hit shows and songs.

The 1940s started out with business-as-usual musical comedy, but Rodgers & Hart’s Pal Joey and Weill and Gershwin’s Lady in the Dark opened the way for more realistic musicals. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma (1943) was the first fully integrated musical play, using every song and dance to develop the characters or the plot. After Oklahoma, the musical would never be the same – but composers Irving Berlin (Annie Get Your Gun - 1946) and Cole Porter (Kiss Me Kate – 1947) soon proved themselves ready to adapt to the integrated musical.

During the 1950s, the music of Broadway was the popular music of the western world. Every season brought a fresh crop of classic hit musicals that were eagerly awaited and celebrated by the general public. Great stories, told with memorable songs and dances were the order of the day, resulting in such unforgettable hits as The King and I, My Fair Lady, Gypsy and dozens more. These musicals were shaped by three key elements:

At first, the 1960s were more of the same, with Broadway turning out record setting hits (Hello, Dolly!, Fiddler on the Roof). But as popular musical tastes shifted, the musical was left behind. The rock musical "happening" Hair (1968) was hailed as a landmark, but it ushered in a period of confusion in the musical theatre.

Composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim and director Hal Prince refocused the genre in the 1970s by introducing concept musicals – shows built around an idea rather than a traditional plot. Company(1970), Follies (1972) and A Little Night Music (1973) succeeded, while rock musicals quickly faded into the background. The concept musical peaked with A Chorus Line (1974), conceived and directed by Michael Bennett. No, No, Nanette (1973) initiated a slew of popular 1970s revivals, but by decade’s end the battle line was drawn between serious new works (Sweeney Todd) and heavily commercialized British mega-musicals (Evita).

The public ruled heavily in favor of the mega-musicals, so the 1980s brought a succession of long-running "Brit hits" to Broadway – Cats, Les Miserables, Phantom of the Opera and Miss Saigon were light on intellectual content and heavy on special effects and marketing.

By the 1990s, new mega-musicals were no longer winning the public, and costs were so high that even long-running hits (Crazy for You, Sunset Boulevard) were unable to turn a profit on Broadway. New stage musicals now required the backing of multi-million dollar corporations to develop and succeed – a trend proven by Disney’s Lion King, and Livent’s Ragtime. Even Rent and Titanic were fostered by smaller, Broadway-based corporate entities.

As the 20th century ended, the musical theatre was in an uncertain state, relying on rehashed numbers (Fosse) and stage versions of old movies (Footloose, Saturday Night Fever), as well as the still-running mega-musicals of the previous decade. But starting in the year 2000, a new resurgence of American musical comedies took Broadway by surprise. The Producers, Urinetown, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Hairspray -- funny, melodic and inventively staged, these hit shows offered new hope for the genre.

Part II

Vaudeville (examples)

Minstrels

Minstrels (a perspective)

"Modern Major General" by Gilbert and Sullivan from Pirates of Penzance

"Yankee Doodle Dandy" by George M. Cohan from Little Johnny Jones

Anything Goes

Ol' Man River

"Oklahoma!"

Everything's up to date in Kansas City from Oklahoma

"Little Bit of Luck" from My Fair Lady

"Im Getting Married in the Morning" from My Fair Lady

"You've Got to be Taught" from South Pacific

Part III

"Cool" by Bernstein and Sondheim from West Side Story

"America" from West Side Story

"Tomorrow Belongs to Me" from Cabaret

"Cabaret"

"Money"

"Trouble" from Music Man

"Let The Sun Shine In" from Hair :20

"Jesus Christ Superstar"

"Steal Your Rock n Roll" from Memphis

"Springtime for Hitler" by Mel Brooks from The Producers

"Hamilton" (2:12)

"Hamilton" What's Next--King George

"Hamilton" You'll be back

"A Chorus Line"

_______________________________________________

Additional Listening

1 "Modern Major General" by Gilbert and Sullivan from Pirates of Penzance

2 "When I Am Laid in Earth" by Purcell (Jessye Norman)

3 "Yankee Doodle Dandy" by George M. Cohan

4 "Finale To Act I" by Puccini from La Bohème (start 5:30)

5 "Cool" by Bernstein and Sondheim from West Side Story

6 "Oh What a Beautiful Morning" by Rogers and Hammerstein from Oklahoma

7 "Nessun Dorma" by Puccini from Turandot

8 "Humming Chorus" by Puccini from Madama Butterfly

9 "Springtime for Hitler" by Mel Brooks from The Producers

10 Rent

1 "Modern Major General" by Gilbert and Sullivan from Pirates of Penzance

2 "When I Am Laid in Earth" by Purcell (Jessye Norman)

3 "Yankee Doodle Dandy" by George M. Cohan

4 "Finale To Act I" by Puccini from La Bohème (start 5:30)

5 "Cool" by Bernstein and Sondheim from West Side Story

6 "Oh What a Beautiful Morning" by Rogers and Hammerstein from Oklahoma

7 "Nessun Dorma" by Puccini from Turandot

8 "Humming Chorus" by Puccini from Madama Butterfly

9 "Springtime for Hitler" by Mel Brooks from The Producers

10 Rent