Lecture: Baroque Music

1600-1750

_________________________________________________________________________

Text Starts Here

Music in the Baroque Age--1600-1750

painting saw the works of Vermeer, Rubens, Rembrandt, and El Greco -- in literature it was the time of Molière, Cervantes, Milton, and Racine -- modern science came into its own during this period with the work of Galileo and Newton. In music, the age began with the trail-blazing works of Claudio Monteverdi, continued with the phenomenally popular music of Antonio Vivaldi and the keyboard works of such composers as Couperin and Domenico Scarlatti, and came to a close with the masterworks of two of the veritable giants of music history, Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel.

Music in the Baroque Age--1600-1750

painting saw the works of Vermeer, Rubens, Rembrandt, and El Greco -- in literature it was the time of Molière, Cervantes, Milton, and Racine -- modern science came into its own during this period with the work of Galileo and Newton. In music, the age began with the trail-blazing works of Claudio Monteverdi, continued with the phenomenally popular music of Antonio Vivaldi and the keyboard works of such composers as Couperin and Domenico Scarlatti, and came to a close with the masterworks of two of the veritable giants of music history, Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel.

Renaissance Reminder:

"O Magnum"

1.

The beginnings of OPERA

Their intent was that this new music should prove more direct and communicative to an audience, as the complex polyphony of the Renaissance could very often obscure the text being sung. (Palestrina Example: Magnificat Primi toni) They instead set a single melodic line against a basic chordal accompaniment, and with this notion of homophony, a new era of music began. The first operas were private affairs composed for the Italian courts. But when in 1637, the first public opera house opened in Venice, Italy, opera became a commercial industry and the genre in which many composers throughout history first tried out new ideas and new techniques of composition.

"O Magnum"

1.

The beginnings of OPERA

Their intent was that this new music should prove more direct and communicative to an audience, as the complex polyphony of the Renaissance could very often obscure the text being sung. (Palestrina Example: Magnificat Primi toni) They instead set a single melodic line against a basic chordal accompaniment, and with this notion of homophony, a new era of music began. The first operas were private affairs composed for the Italian courts. But when in 1637, the first public opera house opened in Venice, Italy, opera became a commercial industry and the genre in which many composers throughout history first tried out new ideas and new techniques of composition.

CLICK on St. Marks Exterior for a Venice ARRIVAL VIDEO

2.

Claudio Monteverdi

Born: Cremona (baptized May 15, 1567)

Died: Venice, November 29, 1643

Monteverdi, the son of a doctor, studied music at the town cathedral in Cremona. He attained his first position as composer and instrumentalist at the court of the Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga of Mantua in 1591. In 1599, he married a singer at the court, Claudia de Cattaneis. The couple had three children before her untimely death in 1607. The composer remained a widower for the rest of his life. Although unhappy and grossly underpaid in Mantua, Monteverdi remained there until the death of Vincenzo in 1612, when the new duke relieved him of his duties.

(Trailor for the modern staging of the opera). He also wrote his Verpers of the Blessed Virgin while in Mantua (a sample of the Vespers)

No doubt, he hoped that the right people would hear his work and offer him a position elsewhere. However, that did not happen. But what did happen was his boss, the Duke, died in 1612, and the new Duke relieved Monteverdi of his duties.

Monteverdi did not remain unemployed for long. Soon after his dismissal in Mantua, he was invited to serve as maestro di cappella at the Basilica of St. Mark in Venice, possibly the second most prestigious musical position in the Western world (the first being Rome). Some believe that while in Mantua, copies of his Verpers made it to Rome and Venice.

Monteverdi remained in Venice until he died in 1643.

St. Mark's Interior Video (2:00)

Although required by his employers at St. Mark's to compose much-sacred music throughout his career, Monteverdi seemed most happy (and his art in most excellent evidence) with secular music. Monteverdi composed and published dozens of madrigals throughout his life, and Zefiro Torna is a wonderful example of his art in that secular form. In this madrigal, Monteverdi uses the standard technique of spinning the melodic lines, one after the other, over a repeated bass figure. One of Monteverdi's undoubted is composed in 1610. Monteverdi's settings here vary between Renaissance polyphony and the newer homophonic sound of the Baroque. He was a master of both forms. The power and fervor of the writing can be heard in the "Lauda Jerusalem" from the Vespers of 1610, with the sound of instruments added to the choir.

Internationally famous through the publication of his madrigals, Monteverdi scaled new artistic heights with the composition of his operas. Many consider him the grandfather of modern opera. His first was L'Orfeo, called by the composer a "fable in music," and was composed for the court of Duke Vincenzo in 1607. Many operas followed, but the music to them was unfortunately lost.

Monteverdi's final opera, written in 1642 when he was in his seventies, remains one of the landmarks of the new genre and his undisputed masterwork. Although the surviving manuscripts consist only of the bass line and vocal parts, comprising mostly dramatic recitativo (melodic declamations over the bass, to which the instrumentalists fill in appropriate harmonies), the ensemble passages are exceptional. The frankly erotic moments between Nero (originally a part for a castrato) and Poppea (soprano) contain music that can still move and amaze modern audiences, as can be heard in the final duet, "Pur ti miro" from L'Incoronazione di Poppea. Opera remained popular throughout the Baroque age, culminating in the stage works of George Frideric Handel.

With his death in 1643, Monteverdi's music fell into oblivion, as it was the nature of the times to perform only the newest music. (Public concerts as we know them did not generally come about until the nineteenth century.) With the early music movements of the twentieth century and the rediscovery of his madrigals and sacred music, Claudio Monteverdi has finally been recognized as one of the true masters of Western music.

Monteverdi's Vespers (beginning then 1:46)

2. Claudio Monteverdi Final duet : "Pur ti muro" Nerone/Poppea

Resources: Translation of “Pur ti miro” by C. MonteverdiMusic: C. Monteverdi Libretto: G.F Busenello

Poppea: I gaze at you

Nero: I delight in you

P: I tighten closer to you

N: I am bound to you

P: I no longer suffer

N: I no longer die

P/N: Oh my life

Oh my treasure.

I am yours

You are my hope

Say it always

My idol

Ever you are

Yes my beloved

Yes my heart

My life, yes

Claudio Monteverdi

Born: Cremona (baptized May 15, 1567)

Died: Venice, November 29, 1643

Monteverdi, the son of a doctor, studied music at the town cathedral in Cremona. He attained his first position as composer and instrumentalist at the court of the Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga of Mantua in 1591. In 1599, he married a singer at the court, Claudia de Cattaneis. The couple had three children before her untimely death in 1607. The composer remained a widower for the rest of his life. Although unhappy and grossly underpaid in Mantua, Monteverdi remained there until the death of Vincenzo in 1612, when the new duke relieved him of his duties.

(Trailor for the modern staging of the opera). He also wrote his Verpers of the Blessed Virgin while in Mantua (a sample of the Vespers)

No doubt, he hoped that the right people would hear his work and offer him a position elsewhere. However, that did not happen. But what did happen was his boss, the Duke, died in 1612, and the new Duke relieved Monteverdi of his duties.

Monteverdi did not remain unemployed for long. Soon after his dismissal in Mantua, he was invited to serve as maestro di cappella at the Basilica of St. Mark in Venice, possibly the second most prestigious musical position in the Western world (the first being Rome). Some believe that while in Mantua, copies of his Verpers made it to Rome and Venice.

Monteverdi remained in Venice until he died in 1643.

St. Mark's Interior Video (2:00)

Although required by his employers at St. Mark's to compose much-sacred music throughout his career, Monteverdi seemed most happy (and his art in most excellent evidence) with secular music. Monteverdi composed and published dozens of madrigals throughout his life, and Zefiro Torna is a wonderful example of his art in that secular form. In this madrigal, Monteverdi uses the standard technique of spinning the melodic lines, one after the other, over a repeated bass figure. One of Monteverdi's undoubted is composed in 1610. Monteverdi's settings here vary between Renaissance polyphony and the newer homophonic sound of the Baroque. He was a master of both forms. The power and fervor of the writing can be heard in the "Lauda Jerusalem" from the Vespers of 1610, with the sound of instruments added to the choir.

Internationally famous through the publication of his madrigals, Monteverdi scaled new artistic heights with the composition of his operas. Many consider him the grandfather of modern opera. His first was L'Orfeo, called by the composer a "fable in music," and was composed for the court of Duke Vincenzo in 1607. Many operas followed, but the music to them was unfortunately lost.

Monteverdi's final opera, written in 1642 when he was in his seventies, remains one of the landmarks of the new genre and his undisputed masterwork. Although the surviving manuscripts consist only of the bass line and vocal parts, comprising mostly dramatic recitativo (melodic declamations over the bass, to which the instrumentalists fill in appropriate harmonies), the ensemble passages are exceptional. The frankly erotic moments between Nero (originally a part for a castrato) and Poppea (soprano) contain music that can still move and amaze modern audiences, as can be heard in the final duet, "Pur ti miro" from L'Incoronazione di Poppea. Opera remained popular throughout the Baroque age, culminating in the stage works of George Frideric Handel.

With his death in 1643, Monteverdi's music fell into oblivion, as it was the nature of the times to perform only the newest music. (Public concerts as we know them did not generally come about until the nineteenth century.) With the early music movements of the twentieth century and the rediscovery of his madrigals and sacred music, Claudio Monteverdi has finally been recognized as one of the true masters of Western music.

Monteverdi's Vespers (beginning then 1:46)

2. Claudio Monteverdi Final duet : "Pur ti muro" Nerone/Poppea

Resources: Translation of “Pur ti miro” by C. MonteverdiMusic: C. Monteverdi Libretto: G.F Busenello

Poppea: I gaze at you

Nero: I delight in you

P: I tighten closer to you

N: I am bound to you

P: I no longer suffer

N: I no longer die

P/N: Oh my life

Oh my treasure.

I am yours

You are my hope

Say it always

My idol

Ever you are

Yes my beloved

Yes my heart

My life, yes

3.

The Baroque Concerto

With the rise of purely instrumental music in the Baroque Age, a flowering of instrumental forms and virtuoso performers to play them arose. One of the earliest masters of the soon-to-be predominant form of the concerto was the Italian composer and violinist Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713). Corelli pioneered the form of the concerto grosso, in which the principle element of contrast between two independent groups of instruments is brought into play. The larger group is called the ripieno and usually consists of a body of strings with harpsichord continuo. In comparison, a smaller group or concertino consists of two to four solo instruments. The various sections of the concerto would alternate between fast and slow tempos or movements. Later composers of the period, such as Johann Sebastian Bach and Antonio Vivaldi, transformed this genre into the solo concerto, in which the solo instrument is equally important to the string orchestra.

Baroque Concerto: Handel's Trumpet Concerto

Baroque Concerto: Corelli

Classical/Romantic Concerto: Clara Schumman (:36)

Classical/Romantic Concerto 2: Grieg Concerto in a Minor (:32)

The Baroque Concerto

With the rise of purely instrumental music in the Baroque Age, a flowering of instrumental forms and virtuoso performers to play them arose. One of the earliest masters of the soon-to-be predominant form of the concerto was the Italian composer and violinist Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713). Corelli pioneered the form of the concerto grosso, in which the principle element of contrast between two independent groups of instruments is brought into play. The larger group is called the ripieno and usually consists of a body of strings with harpsichord continuo. In comparison, a smaller group or concertino consists of two to four solo instruments. The various sections of the concerto would alternate between fast and slow tempos or movements. Later composers of the period, such as Johann Sebastian Bach and Antonio Vivaldi, transformed this genre into the solo concerto, in which the solo instrument is equally important to the string orchestra.

Baroque Concerto: Handel's Trumpet Concerto

Baroque Concerto: Corelli

Classical/Romantic Concerto: Clara Schumman (:36)

Classical/Romantic Concerto 2: Grieg Concerto in a Minor (:32)

4.

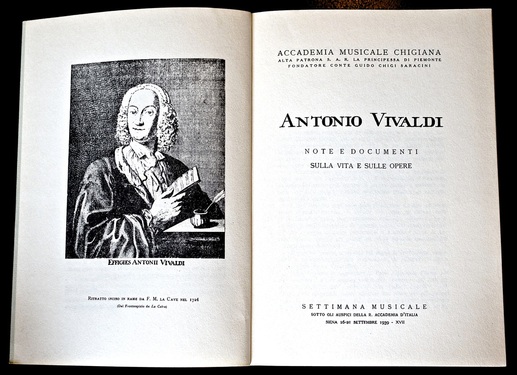

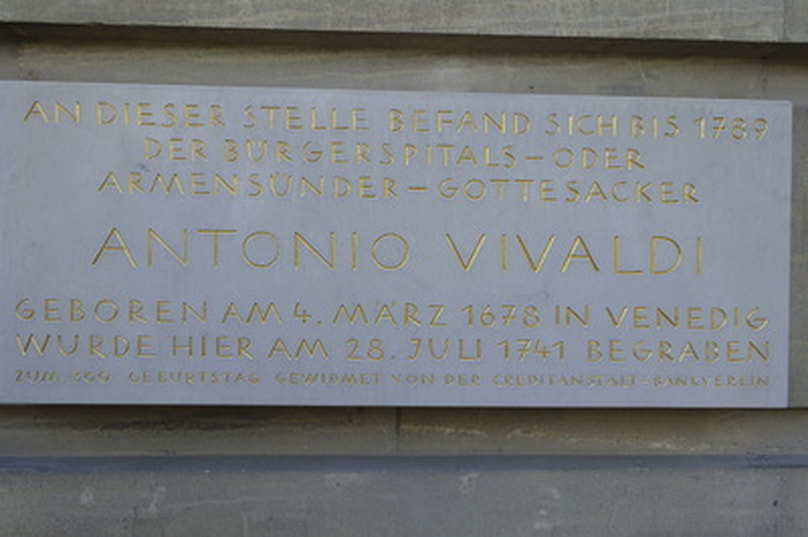

Antonio Vivaldi

Born: Venice, March 4, 1678

Died: Vienna, (buried July 28, 1741)

Another Italian composer and virtuoso violinist, Antonio Vivaldi is remembered today for the enormous number of concertos he composed throughout his lifetime. He most likely learned the violin from his father, himself a violinist at St. Mark's in Venice. Antonio took holy orders to enter the Catholic Priesthood, and became known as "The Red Priest" due to the color of his hair. He became a teacher in Venice at the Ospedale della Pietà in 1703, and later became the director of concerts there. His music was extremely popular, and he traveled a great deal over Europe, spreading his fame as a violinist and composer. During the 1730s, however, his popularity began to abate and in 1738 he was dismissed from the Ospedale. Desperate, he eventually settled in Vienna in 1740, hoping to reclaim his fame. He didn't, and he died there the next year, to be buried in a modest grave near the site where Mozart would be buried 50 years later.

Vivaldi's most famous compositions are the concertos for one or more solo violins and string orchestra, although he composed a great deal of music in other genres, including cantatas, operas, trio sonatas, and others. Indeed, Vivaldi's instrumental works laid the foundation for the development of the concerto into the Classical Period. Among his published collections of string concertos are La Stravanganza, Op. 4, La Cetra, Op. 9, and the ever-popular The Four Seasons, comprised of four concertos, each depicting aspects of the seasons of the year. For instance, the third movement of the Concerto in F, "Autumn," imitates the sounds of a hunt. Vivaldi followed the usual pattern of the era in his concertos by framing a melodious or dramatic slow second movement with fast and lively first and third movements. Of his more than 500 concertos, some 290 are for violin solo and strings or for string orchestra alone. However, Vivaldi also composed a great number of concertos for other instruments and various instrumental combinations. One such work is the sprightly Concerto in G major for two mandolins.

The solo concerto reached its culmination during the later Classical Period in the concertos of Mozart and Beethoven.

Vivaldi's Spring from the Four Seasons

Vivaldi's Staircase, The Metropole, Venice

Leaving Venice

Venice's 2 Golden Ages (Vivaldi Winter/Vivaldi Re-Mix)

Vivaldi's Women at La Pieta in Venice (1st 2 + 14:35 also)

_________________________

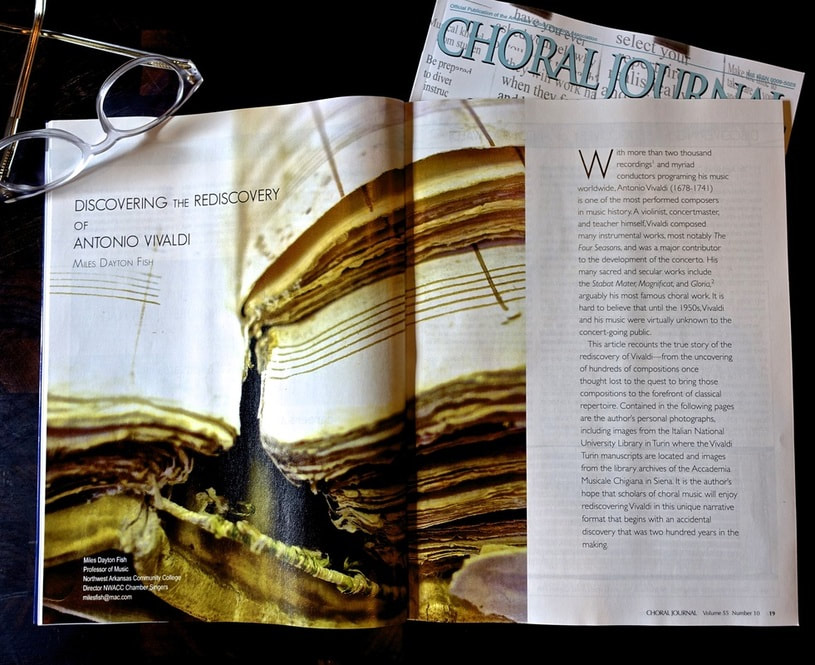

CLICK for M.Fish's

Discovering the Rediscovery of Antonio Vivaldi

Below: 3 misc images

3.Johann Sebastian Bach

Born: Eisenach, March 21, 1685

Died: Leipzig, July 28, 1750

Regarded as perhaps the greatest composer of all time, Bach was known during his lifetime primarily as an outstanding organ player and technician. The youngest of eight children born to musical parents, Johann Sebastian was destined to become a musician. While still young, he had mastered the organ and violin and was also an excellent singer. At the age of ten, both of his parents died within a year of each other. Young Sebastian was fortunate to be taken in by an older brother, Johann Christoph, who most likely continued his musical training. At the age of fifteen, Bach secured his first position in the choir of St. Michael's School in Lüneburg. He traveled little, never leaving Germany once in his life, but held various positions during his career in churches and in the service of the courts throughout the country. In 1703, he went to Arnstadt to take the position of organist at the St. Boniface Church.

During his tenure there, Bach took a month's leave of absence to make the journey to Lübeck (some 200 miles away, a journey he made on foot) to hear the great organist Dietrich Buxtehude. One month turned into five, and Bach was obliged to find a new position at Mülhausen in 1706. That year, he married his cousin, Maria Barbara. Bach remained at Mülhausen for only a year before taking up a post as organist and concertmaster at the court of the Duke of Weimar.

In 1717, Bach moved on to another post, this time as Kapellmeister at the court of Prince Leopold in Cöthen. During the years Bach was in the service of the courts, he was obliged to compose a great deal of instrumental music: hundreds of pieces for solo keyboard, orchestral dance suites, trio sonatas for various instruments, and concertos for different instruments and orchestra. Of these, the most famous are the six concerti gross composed for the Duke of Brandenburg in 1721, and the Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 exemplifies the concerto grosso style in which a small group of instruments (in this case, a small ensemble of strings) is set in concert with an orchestra of strings and continuo. Of Bach's music for solo instruments, the six Suites for violoncello and the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin are among the greatest. The Violin Partita no. 3 contains an example of a popular dance form, the gavotte.

Maria Barbara died suddenly in 1720, having borne the composer seven children. Within a year, Bach remarried. The daughter of the town trumpeter, Anna Magdalena Bach, would prove to be an exceptional companion and helpmate to the composer. In addition, the couple sired thirteen children. (Of Bach's twenty off-spring, ten died in infancy. Four became well-known composers, including Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Christian.) Soon after his second marriage, Bach began looking for another position and eventually took one in Leipzig, where he became organist and cantor (teacher) at St. Thomas' Church. He remained in Leipzig for the rest of his life.

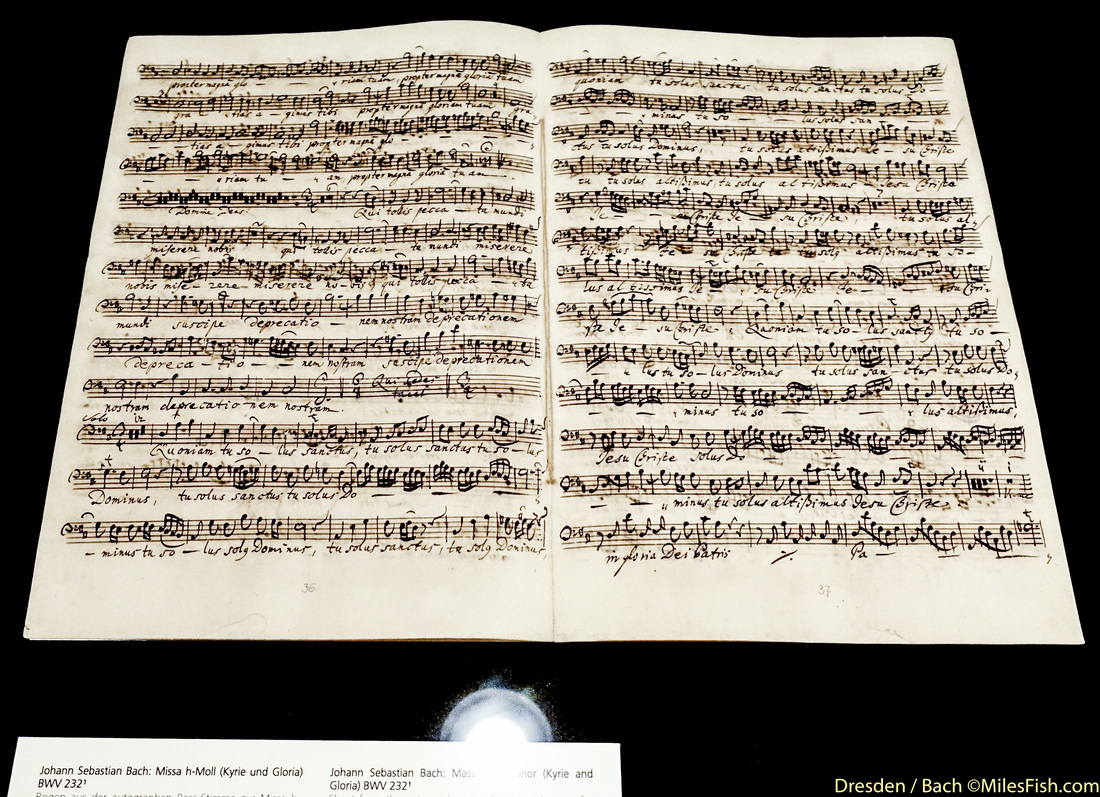

A devout Lutheran, Bach composed a great many sacred works as his duties required when in the employ of the church: well over two hundred cantatas (a new one was required of him every week), several motets, five masses, three oratorios, and four settings of the Passion story, one of which, The St. Matthew Passion, is one of western music's sublime masterpieces. Bach also wrote vast amounts of music for his chosen instrument, the organ, much of which is still regarded as the pinnacle of the repertoire. One such work is the tremendous Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor.

Towards the end of 1749, Bach's failing eyesight was operated on by a traveling English surgeon, the catastrophic results of which were complete blindness. Despite failing health, Bach continued to compose, dictating his work to a pupil. He finally succumbed to a stroke on July 28, 1750. He was buried in an unmarked grave at St. Thomas' Church.

Bach brought to majestic fruition the polyphonic style of the late Renaissance. By and large, a musical conservative, he achieved remarkable heights in the art of fugue, choral polyphony, and organ music, as well as in instrumental music and dance forms. His adherence to the older forms earned him the nickname "the old wig" by his son, the composer Carl Philip Emanuel Bach, yet his music remained very much alive and was known and studied by the next generation of composers. The discovery of the St. Matthew Passion in 1829 by Felix Mendelssohn initiated the nineteenth-century penchant for reviving and performing older, "classical" music. And lead to the discovery of. the Bach B minor Mass. With the death of Johann Sebastian Bach in 1750, music scholars conveniently marked the end of the Baroque age in music.

1 Bach, 10 min. Bio Part I (Class start at 9:00)

Bach, 10 min. Bio Part II (Class all of Part II)

2. Bach, Toccata and Fugue in d minor

Bach, Toccata and Fugue in d minor (FAO)

Bach, Toccata and Fugue (#2 FAO)

3. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto #3, First Movement, Allegro

Dueling Banjos (2:00)

Punch 99 (0:33)

Bach: Brandenburg 3iii

Bach: Brandenburg Punch (0:16)

4. H-moll Messe von J.S.Bach: Dona nobis pacem

Bach's B minor Mass-Dona nobis pacem

Bach's B minor Mass-Dona nobix pacem Atlanta

_____________________________

Cum Sancto Spiritu From bminor

SIDEBAR:

Why did Kate and William choose George? We can only speculate, of course, but Kate and William had a rich heritage of former kings to inspire them for their son's first name. George is a long-standing royal favourite.

It's likely that baby George was named after his great-great-grandfather, King George VI (the Queen's father).

Delving further back into royal dynasties, the name George was first used in 1280 by George I of Bulgaria. George has also been the moniker of choice for many other royal figures: King George VI, Prince George of Denmark, Prince George William of Hanover and George I of Greece. The name did not become popular on our shores until the accession of George I of England in the 18th Century.

Why did Kate and William choose George? We can only speculate, of course, but Kate and William had a rich heritage of former kings to inspire them for their son's first name. George is a long-standing royal favourite.

It's likely that baby George was named after his great-great-grandfather, King George VI (the Queen's father).

Delving further back into royal dynasties, the name George was first used in 1280 by George I of Bulgaria. George has also been the moniker of choice for many other royal figures: King George VI, Prince George of Denmark, Prince George William of Hanover and George I of Greece. The name did not become popular on our shores until the accession of George I of England in the 18th Century.

George Frideric Handel

Born: Halle, February 23, 1685

Died: London, April 14, 1759

Born in the same year and country as Johann Sebastian Bach, young Georg Friederich Händel (the original German spelling of his name) was playing the violin, harpsichord, oboe, and organ by the age of eleven. Drawn to the theater from an early age, Handel went to Hamburg in 1703 and began composing Italian operas. From 1706 to 1710, he sojourned in Italy, where he met Domenico Scarlatti and Arcangelo Corelli and came under the influence of Italian melody. Upon his return to Germany, Handel became Kapellmeister to the Elector Georg of Hanover. Unhappy with his duties there. However, Handel went later in 1710 to London, where Italian opera quickly became all the rage. He produced an opera to great acclaim in London and, having tasted success, reluctantly returned to Germany. Obtaining permission to return to England in 1712, Handel once again composed several operas and some ceremonial music for Queen Anne. The Queen gave the young composer an annual stipend of £200 to keep him in London as court composer. Handel never did return to Hanover. He remained in England for the rest of his life, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1726 and anglicizing his name to George Frideric Handel. A potentially embarrassing situation arose for the composer when Queen Anne died in 1714 and was succeeded by King George I -- the very Georg of Hanover to whose court Handel had never returned! But relations between the two must have remained amicable, for Handel's royal stipend was doubled before too long, on top of which he was granted another stipend from the Princess of Wales.

Throughout his career, Handel continually composed much wonderful instrumental music, including many fine organ concertos, a good amount of keyboard music, and celebratory music such as the suite of airs and dances known as the Water Music, written to accompany a royal barge trip down the Thames in 1717.

Water Music

There is also the Musick for the Royal Fireworks, composed in 1749 to celebrate the peace of Aix-la-Chappelle, which had been declared the previous year. Following the model of Corelli, Handel also completed two sets of concerti grossi, some of the finest examples of the genre from the late Baroque, an example of which is the Concerto Grosso, Op. 6 no. 5. Of course, he was obliged to compose much choral music for the court, too. Among these works are the anthems written for the Duke of Chandos, various odes, and the four majestic Coronation anthems from 1727.

However, these compositions were incidental to Handel's main reason for settling in England: the composition and production of Italian opera for a fashionable and eager audience. He produced them, becoming as involved with the business end of things as with the creative. Beginning with Rinaldo in 1711, Handel composed over forty operas between 1712 and 1741. Many of these met with great success and brought Handel a great deal of fame and money. Some of the more famous of these operas are Giulio Cesare(1724), Alcina (1735), and Serse (1738). Many of these scores contain fine music, and an aria such as "Or la tromba" from Rinaldo illustrates the pomp, grandeur, and vocal virtuosity found in the Italian operas of the late Baroque. Yet, as dramatic entertainment, these works fail to stand up today, primarily because of the ridiculously stilted librettos to which they are set. Indeed, even at that time, it was recognized that some changes had to be made, and within the next thirty years, Christoph von Gluck began implementing those changes. Although Handel's operas were immensely popular when they were written, by the 1730s, public interest in opera had faded considerably. Handel lost a great deal of money and continually attempted to find further success in the genre.

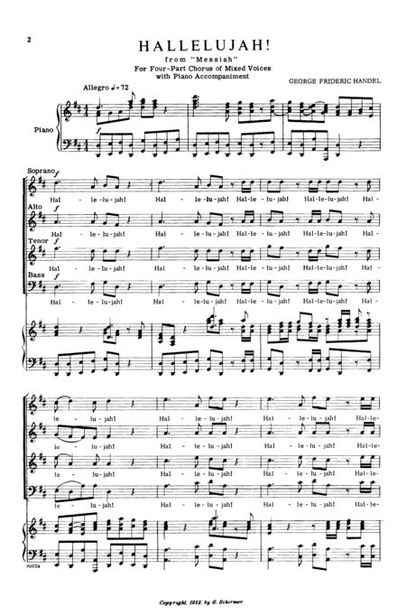

Eager to find a new audience, Handel turned to the composition of oratorio: dramatic, non-staged works for the concert hall, usually with a great deal of choral music, and most often with a Biblical subject, the text in English. His first such composition (Esther) had been written in 1732, and other oratorios followed its success. By 1740, Handel had already composed two of his greatest works in the genre, Saul and Israel in Egypt. Handel infused these Biblical stories with the melody, majesty, and drama he had previously lavished on his operas, and such works as Solomon, Jephthah, Samson, Joshua, Israel in Egypt, and Judas Maccabeusbrought the composer ever more fame and recognition. But Handel's genius is nowhere more evident than in the sublime music he provided for his most famous oratorio, Messiah, which had its premiere in Dublin in 1741. Its success was immediate and resounding, and the work has never been out of the repertory since. The incredible achievements of Handel's oratorios made a deep and lasting impression on English music for the next century, and no native-born musicians could gain a foothold with the public due to their continuing popularity. Not until the Nationalist movement of the late eighteenth century would England produce any composers of lasting international stature.

In 1751, Handel began having trouble with his eyes. He endured three operations on his eyes at the hands of the same surgeon who had unsuccessfully operated on Johann Sebastian Bach, and the results were the same -- complete blindness. Handel kept performing, though, and died a week after suffering a collapse following a performance of Messiah in 1759. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. A biography of Handel was written the year after his death by the Reverend John Mainwaring -- the very first biography of a composer.

End of Text

Examples from Messiah

For Unto Us A Son

Hallelujah

1. "For Unto Us..." all three musical forms

3. Handel's Hallelujah Flash Mob (Macy's)

4. Water Music

5. Hallelujah from Handle's MESSIAH--with nuns

Born: Halle, February 23, 1685

Died: London, April 14, 1759

Born in the same year and country as Johann Sebastian Bach, young Georg Friederich Händel (the original German spelling of his name) was playing the violin, harpsichord, oboe, and organ by the age of eleven. Drawn to the theater from an early age, Handel went to Hamburg in 1703 and began composing Italian operas. From 1706 to 1710, he sojourned in Italy, where he met Domenico Scarlatti and Arcangelo Corelli and came under the influence of Italian melody. Upon his return to Germany, Handel became Kapellmeister to the Elector Georg of Hanover. Unhappy with his duties there. However, Handel went later in 1710 to London, where Italian opera quickly became all the rage. He produced an opera to great acclaim in London and, having tasted success, reluctantly returned to Germany. Obtaining permission to return to England in 1712, Handel once again composed several operas and some ceremonial music for Queen Anne. The Queen gave the young composer an annual stipend of £200 to keep him in London as court composer. Handel never did return to Hanover. He remained in England for the rest of his life, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1726 and anglicizing his name to George Frideric Handel. A potentially embarrassing situation arose for the composer when Queen Anne died in 1714 and was succeeded by King George I -- the very Georg of Hanover to whose court Handel had never returned! But relations between the two must have remained amicable, for Handel's royal stipend was doubled before too long, on top of which he was granted another stipend from the Princess of Wales.

Throughout his career, Handel continually composed much wonderful instrumental music, including many fine organ concertos, a good amount of keyboard music, and celebratory music such as the suite of airs and dances known as the Water Music, written to accompany a royal barge trip down the Thames in 1717.

Water Music

There is also the Musick for the Royal Fireworks, composed in 1749 to celebrate the peace of Aix-la-Chappelle, which had been declared the previous year. Following the model of Corelli, Handel also completed two sets of concerti grossi, some of the finest examples of the genre from the late Baroque, an example of which is the Concerto Grosso, Op. 6 no. 5. Of course, he was obliged to compose much choral music for the court, too. Among these works are the anthems written for the Duke of Chandos, various odes, and the four majestic Coronation anthems from 1727.

However, these compositions were incidental to Handel's main reason for settling in England: the composition and production of Italian opera for a fashionable and eager audience. He produced them, becoming as involved with the business end of things as with the creative. Beginning with Rinaldo in 1711, Handel composed over forty operas between 1712 and 1741. Many of these met with great success and brought Handel a great deal of fame and money. Some of the more famous of these operas are Giulio Cesare(1724), Alcina (1735), and Serse (1738). Many of these scores contain fine music, and an aria such as "Or la tromba" from Rinaldo illustrates the pomp, grandeur, and vocal virtuosity found in the Italian operas of the late Baroque. Yet, as dramatic entertainment, these works fail to stand up today, primarily because of the ridiculously stilted librettos to which they are set. Indeed, even at that time, it was recognized that some changes had to be made, and within the next thirty years, Christoph von Gluck began implementing those changes. Although Handel's operas were immensely popular when they were written, by the 1730s, public interest in opera had faded considerably. Handel lost a great deal of money and continually attempted to find further success in the genre.

Eager to find a new audience, Handel turned to the composition of oratorio: dramatic, non-staged works for the concert hall, usually with a great deal of choral music, and most often with a Biblical subject, the text in English. His first such composition (Esther) had been written in 1732, and other oratorios followed its success. By 1740, Handel had already composed two of his greatest works in the genre, Saul and Israel in Egypt. Handel infused these Biblical stories with the melody, majesty, and drama he had previously lavished on his operas, and such works as Solomon, Jephthah, Samson, Joshua, Israel in Egypt, and Judas Maccabeusbrought the composer ever more fame and recognition. But Handel's genius is nowhere more evident than in the sublime music he provided for his most famous oratorio, Messiah, which had its premiere in Dublin in 1741. Its success was immediate and resounding, and the work has never been out of the repertory since. The incredible achievements of Handel's oratorios made a deep and lasting impression on English music for the next century, and no native-born musicians could gain a foothold with the public due to their continuing popularity. Not until the Nationalist movement of the late eighteenth century would England produce any composers of lasting international stature.

In 1751, Handel began having trouble with his eyes. He endured three operations on his eyes at the hands of the same surgeon who had unsuccessfully operated on Johann Sebastian Bach, and the results were the same -- complete blindness. Handel kept performing, though, and died a week after suffering a collapse following a performance of Messiah in 1759. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. A biography of Handel was written the year after his death by the Reverend John Mainwaring -- the very first biography of a composer.

End of Text

Examples from Messiah

For Unto Us A Son

Hallelujah

1. "For Unto Us..." all three musical forms

3. Handel's Hallelujah Flash Mob (Macy's)

4. Water Music

5. Hallelujah from Handle's MESSIAH--with nuns

BRIEF REVIEW

The Baroque was a time of great intensification of past forms in all the arts:

Four Big Names in the Baroque era were Monteverdi, Vivaldi, JS Bach, and Handel.

In the last years of the sixteenth century, a group of musicians and literati in Florence, Italy, experimented with a new method of composing dramatic vocal music, modeling their ideas after the precepts of ancient Greek theater. The Florentine Camerata called this new form of musical-dramatic entertainment opera.

Soon after his dismissal in Mantua, Monteverdi was invited to serve as maestro di cappella at the Basilica of St. Mark in Venice, possibly the second most prestigious musical position in the Western world (the first being Rome). He became internationally famous through the publication of his madrigals and his popular operas.

With the rise of purely instrumental music in the Baroque Age, a flowering of instrumental forms and virtuoso performers to play them arose. One of the earliest masters of the soon-to-be predominant form of the concerto was the Italian composer and violinist Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713).

Another Italian composer and virtuoso violinist, Antonio Vivaldi is remembered today for the enormous number of concertos he composed throughout his lifetime. He most likely learned the violin from his father, himself a violinist at St. Mark's in Venice. He is best known today for his concertos “The Four Seasons.” Of his more than 500 concertos, some 290 are for violin solo and strings or for string orchestra alone. However, Vivaldi also composed a great number of concertos for other instruments and various instrumental combinations.

Regarded as perhaps the greatest composer of all time, JS Bach was known during his lifetime primarily as an outstanding organ player and technician. Bach brought to majestic fruition the polyphonic style of the late Renaissance.

At the age of ten, both of his parents died within a year of each other. Young Sebastian was fortunate to be taken in by an older brother, Johann Christoph, who most likely continued his musical training. At the age of fifteen, Bach secured his first position in the choir of St. Michael's School in Lüneburg. Hecompose a great deal of instrumental music: hundreds of pieces for solo keyboard, orchestral dance suites, trio sonatas for various instruments, and concertos for different instruments and orchestra.

After his death, the discovery of the St. Matthew Passion in 1829 by Felix Mendelssohn initiated the nineteenth-century penchant for reviving and performing older, "classical" music. It led to the revival of Bach’s B minor Mass.

Born in the same year and country as Johann Sebastian Bach, young Georg Friederich Händel (the original German spelling of his name) was playing the violin, harpsichord, oboe, and organ by the age of eleven. Handel moved from Germany to England; his main reason for settling in England was the composition and production of Italian opera for a fashionable and eager audience. He produced them, becoming as involved with the business end of things as with the creative.

But Handel's genius is nowhere more evident than in the sublime music he provided for his most famous oratorio, Messiah, which had its premiere in Dublin in 1741.

The Baroque was a time of great intensification of past forms in all the arts:

Four Big Names in the Baroque era were Monteverdi, Vivaldi, JS Bach, and Handel.

In the last years of the sixteenth century, a group of musicians and literati in Florence, Italy, experimented with a new method of composing dramatic vocal music, modeling their ideas after the precepts of ancient Greek theater. The Florentine Camerata called this new form of musical-dramatic entertainment opera.

Soon after his dismissal in Mantua, Monteverdi was invited to serve as maestro di cappella at the Basilica of St. Mark in Venice, possibly the second most prestigious musical position in the Western world (the first being Rome). He became internationally famous through the publication of his madrigals and his popular operas.

With the rise of purely instrumental music in the Baroque Age, a flowering of instrumental forms and virtuoso performers to play them arose. One of the earliest masters of the soon-to-be predominant form of the concerto was the Italian composer and violinist Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713).

Another Italian composer and virtuoso violinist, Antonio Vivaldi is remembered today for the enormous number of concertos he composed throughout his lifetime. He most likely learned the violin from his father, himself a violinist at St. Mark's in Venice. He is best known today for his concertos “The Four Seasons.” Of his more than 500 concertos, some 290 are for violin solo and strings or for string orchestra alone. However, Vivaldi also composed a great number of concertos for other instruments and various instrumental combinations.

Regarded as perhaps the greatest composer of all time, JS Bach was known during his lifetime primarily as an outstanding organ player and technician. Bach brought to majestic fruition the polyphonic style of the late Renaissance.

At the age of ten, both of his parents died within a year of each other. Young Sebastian was fortunate to be taken in by an older brother, Johann Christoph, who most likely continued his musical training. At the age of fifteen, Bach secured his first position in the choir of St. Michael's School in Lüneburg. Hecompose a great deal of instrumental music: hundreds of pieces for solo keyboard, orchestral dance suites, trio sonatas for various instruments, and concertos for different instruments and orchestra.

After his death, the discovery of the St. Matthew Passion in 1829 by Felix Mendelssohn initiated the nineteenth-century penchant for reviving and performing older, "classical" music. It led to the revival of Bach’s B minor Mass.

Born in the same year and country as Johann Sebastian Bach, young Georg Friederich Händel (the original German spelling of his name) was playing the violin, harpsichord, oboe, and organ by the age of eleven. Handel moved from Germany to England; his main reason for settling in England was the composition and production of Italian opera for a fashionable and eager audience. He produced them, becoming as involved with the business end of things as with the creative.

But Handel's genius is nowhere more evident than in the sublime music he provided for his most famous oratorio, Messiah, which had its premiere in Dublin in 1741.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=icZob9-1MDwListening to Music in the Baroque Period

(click to listen/view a Youtube)

1. Antonio Vivaldi

SPRING

2. J.S. Bach

Air on the G String (Suite No. 3, BWV 1068)

3a. J.S. Bach (Petzold)

Minuet in G

3b. J.S. Bach (Petzold)

Minuet in G

4. G.F. Handel

"For Unto Us..." best of all forms to date (monophonic, polyphonic, homophonic)

(click to listen/view a Youtube)

1. Antonio Vivaldi

SPRING

2. J.S. Bach

Air on the G String (Suite No. 3, BWV 1068)

3a. J.S. Bach (Petzold)

Minuet in G

3b. J.S. Bach (Petzold)

Minuet in G

4. G.F. Handel

"For Unto Us..." best of all forms to date (monophonic, polyphonic, homophonic)

OForm/Texture inclass Quiz

You have 5 choices to use

1. monophonic

2. Organum 2 voices

3. Organum MORE than 2 voices

4. Polyphonic

5. Homophonic

Example "A"

Example "B"

Example "C"

Example "D"

Example "E"

Example "F"

Example "G"

Example "H"

Example "I"

Example "J"

Example "K"

Example "L"

Example "M"

Pre-test

Monophonic

Monophonic

Organum 2 voices

Organum more than 2 voices

Polyphonic

Homophonic

Homophonic